West African Democracy Part 2: Backsliding in the Region

14 Jan 2021

Part 2 of our Africa mini-series looks at the regional democratic decline of West Africa and its causes, including an ageing crop of leaders, a subtle change to what the Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) mission and goals are and the influence of Beijing through loans. The report also looks the regional exception, Ghana, and explores whether the country bucks the trend of those around it or is also seeing a backwards slide.

Executive Summary

The first installment of our West Africa mini-series focused on how two recent elections, one held in Guinea (Conakry) and the other held in Cote d’Ivoire, could both be seen as representative of a wider democratic malaise that has set in across the West African region. Indeed, Figure 1 shows that the majority of African countries are seen as either partially free democracies (yellow) or unfree countries (red). While there are some notable exceptions with a number of free democracies (green), the majority of the continent is either partially free or classed as unfree. The notable exception in the West Africa region, the area highlighted by the black outline, remains Ghana.

Regression in the region has happened in a relatively short space of time. As mentioned in part one of our series, in Freedom House’s Global Freedom Status rankings, five of the 12 worst performers are all now located in West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, and Nigeria). Alongside this, Senegal and Benin both fell from the “Free” category to being “Partially Free” between the 2019 and 2020 reports. This second report in the series will examine this regional decline and try to examine some reasons why it may be occurring.

Regional Democratic Decline

The region’s decline in democracy, which was demonstrated by the elections in Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire, really began two or three years ago. However, this decline has been amplified by more recent regional manifestations.

In 2018, for instance, Senegal saw controversial changes to the requirements that limit who can stand as a candidate for election, while in Nigeria, seen as Africa’s largest democracy, the President rejected multiple attempts at electoral reform. These early signs were little acknowledged by the wider international community. It was only after a troubled year of elections across the region in 2019 that concerns began to develop. For instance, in Senegal, opposition candidates were jailed, and in Nigeria, voting in national and regional elections was postponed and the resulting election had significant irregularities.

These incidents should have served as early warning lights for the democratic backsliding that many other countries in the West Africa region experienced in 2020.

In The Gambia, the transitional government announced that President Barrow will no longer uphold his original commitment of serving three years as leader in the transition between dictatorship and civilian rule. Alongside this, in Togo, President Faure Gnassingbé claimed victory in an election marred by widespread irregularities, a partial internet and communications blackout, and the blocking of election observers. This victory also, incidentally, saw him begin a fourth term in office despite the constitution stating all presidents have a two-term limit.

Conflict-troubled Mali, which is the historical source for much of the West African insecurity, was host to a military coup in August after nationwide mass protests erupted against the government of President Keita. This coup saw ECOWAS impose sanctions and demanded the return of civilian rule on the country. In the aftermath of this, it was announced that a new transition government would be created, and that national elections would be held in 18 months. Whilst this satisfied ECOWAS, the fact that some of the largest pre-coup protest groups have been left out of the government is likely to lead to questions as to how much civilian power the new transitional government actually has. It remains to be seen whether the new military leaders of the country will abide by their announced declaration that free and fair elections will take place in 2021. Additionally, the fact that it is believed that the new military junta organised the release of at least 200 jihadist fighters, in exchange for the release of several high-profile hostages, will likely raise fears about a resurgence of cyclical insecurity in the region.

A good example of the underlying malaise in the region is Benin. Until recently, the country had been held in high regard, and ranked highly in several measures such as press freedom, democratic participation, and civil liberties. Despite this, the country saw a significant decline in its democratic credentials in recent years. In the last two years, there has been a spate of politically motivated prosecutions against opposition and anti-government leaders, which culminated in an internet blackout and the barring of opposition candidates running in parliamentary elections. This then resulted in widespread post-election violence and led to the repression of civil society.

However, despite Benin’s feted democratic success, the country’s democracy has been fragile for some years. Corruption and clientelism have long been endemic, as they have in many African countries, bribes are common and kinship politics is widespread, all of this has meant that party politics has been fractured, resulting in over 200 political parties. This resulted in recent elections, such as in 2011 and 2016, being delayed, with widespread disruption and accusations of irregularities. Previous presidents of the nation have also not been immune to “Third-termism” as discussed in part 1 of our mini-series.

Finally, Sierra Leone, which was one of the region’s emerging democracies following its long civil war in the 1990s, is seeing a resurgence in political violence. A 2020 survey in the country found that 80 percent of Sierra Leoneans believed that politics “often” or “always” leads to violence. This feeling is matched by the fact that in the West Africa region, Sierra Leone now has the highest rates of political violence of any country that does not have an officially recognised conflict within its borders. This statistic can be seen as an indicator that in the last ten years Sierra Leone has been regressing away from the country that reached peaceful stability in the aftermath of a brutal civil war, and back towards the latter situation.

Causes of the Democratic Decline

One of the main causes of the decline could potentially be that leaders in the region just generally appear much less willing to intervene to defend democratic norms in the region. Former leaders, especially those of Nigeria, were willing to even deploy troops and Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) missions to support democracy in the region. Indeed, the fact that in recent times ECOWAS has not been vocal about regional leaders running for third terms on shaky constitutional ground, can be seen as evidence of this. Alongside, this, Nigeria, which used to be one of the more active nations in the region in trying to uphold democratic norms, is less willing to intervene than it previously was. This is perhaps due to its focus on internal issues in recent years, with the ongoing battle in its north against Boko Haram and in the south against a potential new Biafran separatist movement. Further evidence for this can be seen in the ECOWAS reaction to the Cote d’Ivoire election. Despite the ongoing protests over the election in the region, the 15-member bloc sent Ouattara its congratulations on his victory, despite the death of 50 people in post-election violence and large-scale clashes and fighting across the country in the weeks succeeding the election.

It is possible that ECOWAS is evolving to become more than a simple economic bloc, and that, as a result, ECOWAS member states are increasingly hesitant to criticise events in other member states, in case the state under scrutiny decides to leave. African states have always historically been reluctant to criticise each other in case it is seen as a sign of western influence or pressure, and since independence have often tried to follow pan-Africanism and the idea of African solutions for African problems.

Effectively this means that ECOWAS members are prioritising maintenance of stability and a semblance of unity despite a number of diverging states. If this is the case, then ECOWAS should be wary of the path that the EU, with more robust democratic states, has trodden, with regards to member states such as Poland and Hungary openly flouting membership requirements. If the EU is not immune to such troubles, then ECOWAS likely is not either.

Alternatively, it is also possible that as many states have seen declines in democratic standards, they are all hesitant to criticise each other’s conduct, in case it sparks protests and demonstrations in their own state, against their own increasing democratic deficits.

A second potential reason for the shift is that a number of regional leaders come from more technocratic or economic backgrounds than previous generations have done, and therefore focus less on democracy building, and more on economic issues than political ones, and this shift in focus can be seen through the fact that those in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, are seeking deeper economic integration through ECOWAS and the eventual launch of a regional currency, which has been long delayed since 2003. ECOWAS, and regional leaders, can be said to have abdicated the championing of democracy in favour of perceived regional stability and economic growth.

This potential recalibration in priorities is not perhaps the only economic reason for the democratic decline in the region. More often than not, such economic plans and visions are funded by Chinese loans. Indeed between 2000 and 2017, Chinese loans to West Africa, totalled 18.2 billion USD, with Ghana and Nigeria being the two largest beneficiaries with 4.8 billion USD and 3.5 billion USD respectively. Other countries in West Africa, however, have received less money, but as a proportion of their GDP it has been significantly more, for instance, Togo as of 2020 owed 17.4 percent of its GDP to China, and Benin 10.8 percent. The majority of these Chinese loans go towards funding vast infrastructure projects in the region such as transportation (roads, railways, ports) and electrical grids, even if the economic case and future for such projects are questionable. Examples include Nigeria’s new Standard gauge rail network, and Chinese funded expansion of ports in Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Cote d’Ivoire.

Chinese financial aid and loans are often seen as more attractive to African nations than money from Western governments and western-backed multi-lateral institutions. This is because on the surface they often have more favourable terms, and often come with less stringent rules about transparency and governance. As such, the rise of Chinese loans (which often lack stipulations on human rights, democratic norms, and “rule of law”, that are often attached to Western loans) to Africa as a whole, but in this instance particularly West Africa, have helped to drive down democratic standards in the region.

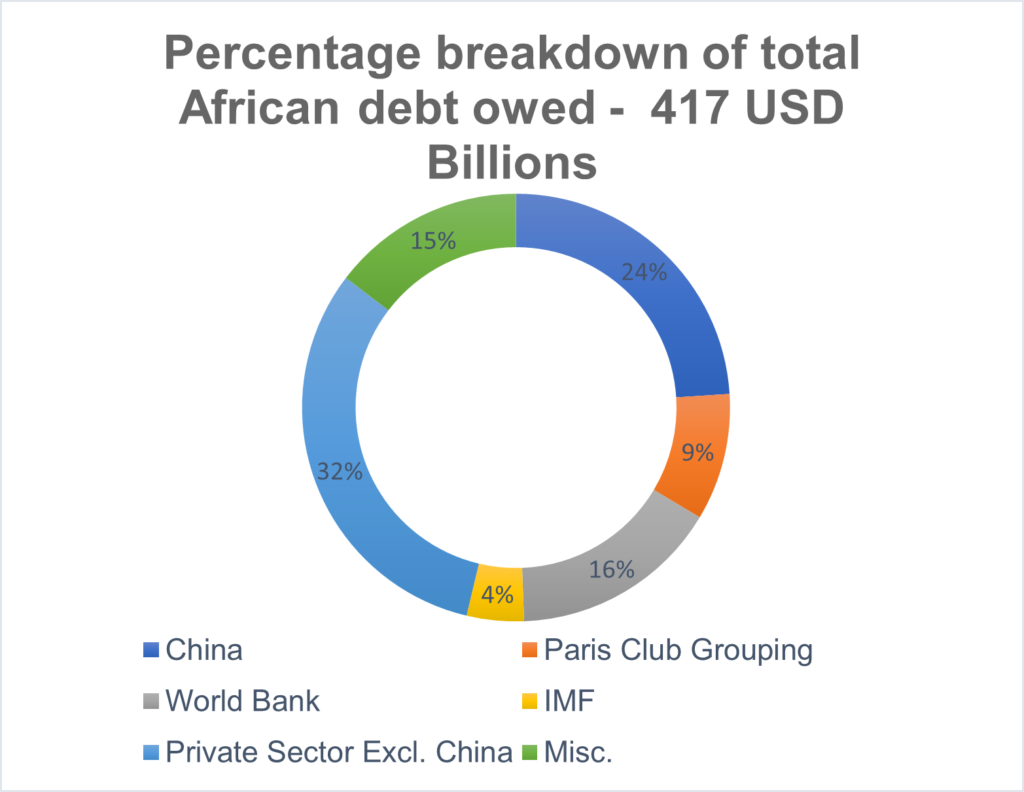

Further evidence for this comes from the fact that it is now estimated that China alone lends more to Africa than the World Bank. Research by the Jubilee Debt Foundation shows that across all of Africa, 24 percent of all debt across the continent is owed to China. Non-Western institutions or group of nations do not come near to reaching such a percentage, with the World Bank, for instance, owning 16 percent of all African Debt.

Yet the presence of Chinese loans, which have been accused of being a new form of “neo-colonialism” also perhaps do not account fully for the democratic decline. Another factor could be down to generational expectations. It is now 31 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, a symbolic moment which for many was the moment of victory and triumph for free-market liberal democracy over the communist alternative. The years since however, have arguably showcased the shortcomings of the liberal democratic system, whilst to onlookers, the seemingly unstoppable economic rise of China, served to demonstrate the benefits of a more authoritarian system of governance. The rise in authoritarianism can been seen across the world from in a number of countries, including those once regarded as emerging model democracies. Taken in this light then, it is perhaps not surprising that in West Africa where democracy has always been on shaky ground that a number of countries are seeing a return more authoritarian ways of governance.

Another factor likely playing into the regions democratic backsliding is the fact that several of the countries in the region are effectively gerontocracies. The region has an ageing political class linked back to the eras of the cold war and independence. This ageing crop of leaders stand in contrast to the increasing youthful populations which they rule over. In Niger, for instance, the median age is around 15 years and its President, Mahamadou Issoufou is 68. Nigeria has an age gap of 57 years between its average age of 18 years and President Buhari’s age of 77. The increasingly urban and well educated young across Africa, are less likely to tolerate such large disconnects between them and their leaders. This can be seen from the protests at the end of 2020 in Nigeria, where protests against police brutality morphed into wider anti-government protests, and also in the protests in Mali last year which resulted in the Malian Coup.

These younger populations increasingly seek greater representation in government, greater transparency, and a more secure basis for the freedoms they increasingly expect. This generational divide could have a number of profound consequences in the region. Elderly leaders in some of the more authoritarian states could use the levers of the state they control to increase repression of civil society and general populations in an effort to head off their any challenge to their leadership. Alternatively, the region could reach a breaking point, a little like North Africa did in the early 2010s, where mass popular protests fuelled by well educated, but jobless and disillusioned youthful populations led to the toppling of a number of longstanding authoritarian dictatorships with varying successful outcomes.

Until this generational divide is breached it is likely that most countries in the region will continue to suffer the effects of gerontocracy as outlined above, and for those that are able, namely the wealthy educated middle classes, they will increasingly seek to move abroad to countries in North America and Europe where they feel their hopes and aspirations will be better met. In testament to this, Henley and Partners, a consultancy which advises on citizenship through investment schemes, has recently opened an office in Lagos, Nigeria, where demand for second citizenship or relocation services is seen to be strong, as a new wave of emigration amongst the middle and educated classes is emerging. Canada, the United Kingdom, and the US are the three top destinations. Nigerian Immigration to Canada has increased 28-fold for instance since 2015. Nigeria is the wealthiest and largest West African country, and thus is often seen as the trendsetter, it is therefore likely that similar trends are playing out across Africa, although many of the poorer will likely not be using investment schemes and skilled worker visas to flee the region but will instead end up in the hands of people smugglers. There is also an internal wave of migration as those without the means to seek a new life abroad, opt at least to try and seek a new lew in the more developed countries in the region, a factor which is likely behind a wave of violence and xenophobia in South Africa, which in 2019 saw Nigerian businesses in the country looted, and in 2020 saw protestors demanding that foreigners, including those from West African nations, leave the country

The Bright Light of Ghana?

There is one country in the region that, at the time of writing, appears to be weathering the storm. That country is Ghana. Having gained independence in 1957, Ghana has held free and fair elections under a multiparty system since 1992 and is seen as one of the most politically stable and peaceful countries in Africa. The most recent election took place in December 2020 and was called the year’s most boring election, as there was little violence and no vote-rigging (or claims of it). Democratic participation in the country is high as well with 60.25% of voters casting ballots in the election.

The elections results were interesting. In the Presidential poll, where the result was closer than anticipated, the losing candidate, Mr Mahama, has declared he will seek to overturn the results. Yet, for the parliamentary elections, Mr Mahama, and his National Democratic Party, may have taken enough seats from their National Patriotic party to result in a hung parliament. If this is true, then it shows that voters in Ghana have begun to use a tactic known as “split ticketing” voting for different parties for different roles in the same electoral process, which indicates the strength and maturity of Ghana’s democratic system, and also the lack of any major partisan split in the electorate.

Despite this apparent success, however, it too is being buffeted by the political ill winds in the region. This is now the second time that a presidential election result has been challenged by the losing party, and deep political division has begun appearing as a result. It was also reported that post-election violence, a rare occurrence in Ghana, left five dead. The challenge will be heard by Ghana’s Supreme Court. It has already been announced that to help maintain transparency the forthcoming Supreme Court hearings will be broadcast live on TV. It will be hoped by many election watchers, that Ghana’s democracy and judicial system are mature enough to effectively deal with this challenge in a nonpartisan and fair manner.

Yet, the bright light may already be dimmer than people hope. This is because on the evening of 7 January, whilst the world’s attention was captivated by events in Washington DC, an equally shocking moment which was captured live on Ghanaian TV, the military invaded the Ghanaian Parliament. This intervention came as lawmakers from the two main parties, the NDP and the NPP came to blows during what should have been a routine vote to install a new speaker of the house. The footage of the scenes in Parliament, complete with the eventual military intervention, underscored the fact that despite its lauded status, Ghana’s democracy is likely suffering from the forces afflicting much of Western Africa, and in the words of Ghana’s former President John Dramani Mahama made the nation appear to be a “banana republic and a politically unstable country”.

Conclusion

If even Africa’s most celebrated, and strongest democracy can begin to fall prey to the troubles which have blighted its weaker neighbours for the last decade or so, then this should be taken as a sign that the regional crisis of democracy truly runs deep. Given Ghana’s past history and the fact that its democratic institutions are seen as fairly mature, and resilient, the country will be watched to see how to fend off these potential threats to its democracy, and in the process, it may offer a pathway that its neighbours could seek to emulate.

The region is suffering an acute crisis of democratic governance. The reasons for this are manifold. The rise of Chinese loans without pre-conditions around governance are likely leading to a plateauing, if not a decline in standards of governance, and democracy. They are also likely to be fuelling corruption as Chinese loans are often opaquer than their western counterparts. Endemic corruption is corrosive to good governance. Yet the decline can’t be laid all at the foot of China. The disconnect between the ageing leaders and the interests they represent has led to a profound lack of hope among their young citizens.

Finally, the growth in the regional insecurity has a profound effect on the levels of democracy, the rise of insecurity and the region’s democratic decline are closely linked, with one driving the other in a deepening downward cycle. The next and final part of the series will look at the second half of the region’s problems, namely the increasing insecurity that a number of the states in the region face. For neither the insecurity nor the democratic deficit can be solved alone. They must both be looked at together, within the constraints of the various historical processes that the various West African states have been exposed to, for a stable and permanent solution to be found.

Continue Reading

West African Democracy and Security Part 1: Progress or Regression?

West African Democracy and Security Part 3: The Rise of Insecurity

The Sahel Deterioration and Violence in West Africa in 2024

Examine the recent elections in Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea, emblematic of the broader democratic regressions afflicting the region. These pivotal elections underscore the escalating democratic declines plaguing much of West Africa.

Examine the intertwining of the security decline in the region with escalating insecurity, where each contributing factor fuels the other in a concerning cycle.

The Sahel, characterised by growing instability triggered by poverty, food insecurity, water scarcity and challenges presented by terrorism, rebel groups and poor governance, faces threats of further deterioration of security in 2024.