Maritime Update – Gulf of Oman Attack

21 Jun 2019

One week after the attack in the Gulf of Oman, it remains unclear who the perpetrator is. Regardless, the attack constituted the second instance in a month where oil and gas vessels were targeted in the Arabian Peninsula area.

Executive Summary

One week after the attack in the Gulf of Oman, it remains unclear who the perpetrator is. Regardless, the attack constituted the second instance in a month where oil and gas vessels were targeted in the Arabian Peninsula area. What is clear, is that the episode greatly increased the already heightened tensions in the region and could cause long-term ramifications within both the maritime and the oil and gas industry.

The latest attack, coupled with the incident that occurred in May in Fujairah, have highlighted the vulnerability of merchant vessels whilst transiting high risk areas. Oil tanker owners are already facing increased insurance costs if using ports in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Reports are already circulating that the war risk insurance premiums that owners are required to pay each time they go to the Persian Gulf have now surged to at least 185,000 USD for supertankers.

Update

As it stands, on 13 June, explosions occurred on two underway tankers in the Gulf of Oman; the Front Altair and the Kokuka Courageous. The incident is, beyond all reasonable doubt, some form of attack. This was almost certainly carried out using limpet mines placed above the waterline on the side of both vessels; with photos depicting one unexploded mine on the side of one of the vessels.

The Japanese owned Kokuka Courageous and Norwegian owned Front Altair have since been towed to United Arab Emirates waters. The explosions on the Front Altair resulted in quite extensive damage from the resulting fire; however, the fire did not appear to result in any significant damage to the ship’s cargo or fuel load. The Kokuka Courageous is understood to have taken far less damage, with a single breach “above the waterline”. Video footage released by the United States depicts what they alleged are Iranian Revolutionary Guards removing the unexploded limpet mine on the vessel.

As a result of the attack, six vessels have now been damaged in the region in a little over a month:

| Vessel | Owner | Flag | Damage location | Capacity (barrels) |

| Al Marzoqah | Bahri | Saudi Arabia | Stern & below waterline | 713,000 |

| Andrea Victory | MSEA Tankers | Norway | Stern & below waterline | 325,000 |

| Amjad | Bahri | Saudi Arabia | Side & below waterline | 2,059,000 |

| A Michel | Al Arabia Bunkering Co | United Araba Emirates | Side & below waterline | 43,000 |

| Front Altair | Frontline | Marshall Islands | Starboard & above waterline | 777,000 |

| Kokuka Courageous | Kokuka Sangyo Co | Panama | Starboard & above waterline | 200,000 |

The Kokuka’s owner’s assessment that “flying projectiles” had been used appears to be unfounded; with little evidence supporting the assessment. It is likely that those who planted the mines may have flown drones at the time of detonation, in an effort to monitor or assess the damage that the ships sustained, or to ensure that all the mines detonated successfully.

The attack, coupled with the one in Fujairah, has raised the tensions in the region, which have been further stoked by the shooting down of an American drone by Iranian Revolutionary Guards on 20 June. The drone is understood to have been operating in international airspace at the time of the incident.

Lloyds Joint War Risk Committee, which details areas of heightened insecurity for marine insurers, has recognised the “perceived heightened risk across the region” to shipping. It has included the Gulf of Oman in a list of areas of enhanced risk, essentially designating the waterway a warzone.

Solace Global Comment

While details of the attack are increasingly emerging, it remains unclear who might have executed it. All stakeholders in the region are expressing suspicions based on traditional allegiances/factions/conflict lines, with the US officially accusing Iran of being behind both this and the Fujairah attacks. The governments of Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United Kingdom are understood to be in support of this accusation. Adversely, the Iranian government has strongly denied culpability and instead apportioned blame at the United States.

It is likely whoever carried out the attacks, will remain unclear. Speculation exists about whether the attacks were sanctioned or even carried out by Tehran, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, or if it was a “false flag” operation carried out by Saudi Arabia, UAE, US, or even Israel. The number of theories circulating online and in the political sphere on the incidents have easily entered the double figures.

The proximity to the Iranian coast means that Tehran would have had the easiest access to the vessels. Iran’s oil exports have all but dried up since the US imposed renewed sanctions. Exports are believed to be at a lower level than before 2012 – under the previous sanctions. However, the mines could have also been placed on the vessels long before they came into close proximity to Iranian waters. It also would be “surprising” for Iran to carry out such a blatant “attack” whilst hosting Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. European leaders have urged caution, citing the Gulf of Tonkin incident; an incident off the Vietnamese coast that the US used as a justification for greater involvement in the War in Vietnam.

The Houthi rebels in Yemen are another possible perpetrator. In July 2018, Saudi Arabia suspended its oil shipments through the Red Sea following an attack on two of its crude tankers reportedly conducted by Yemeni Houthi rebels. Houthi rebels also regularly target Saudi oil facilities with drone and rocket strikes, most recently succeeding in damaging the Saudi airport of Abha. Moreover, as the Houthis are widely seen as an Iranian proxy, their involvement would not completely dissolve Tehran of involvement.

The Islamic State militants are also a possible culprit, although a highly remote possibility at this time, the group members are sworn enemies of both Iran and the US and may be trying to stoke conflict between the two countries, or between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Any conflict in the region is likely to heighten the number of possible recruits and would likely result in increased immigration to Europe; with migrant camps being a perfect recruitment ground for terrorist groups.

In the wider region, there has been a range of attacks on Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and international oil corporations in the region that support the narrative that, while Tehran may not have been behind the attacks, they may have played a part in them; especially given the large number of attacks carried out by the Houthis in Yemen. Since March 2018, there have been at least 10 reported attacks on oil facilities or vessels, with further attacks also occurring on UAE vessels, Saudi infrastructure, international oil company headquarters in Iraq.

What Next?

Until the culprits are found, with actual proof and not circumstantial evidence, further attacks are likely to take place in the coming weeks and months. The tensions in the region are high, with the shooting down of a US drone on 20 June only likely to increase the existing tensions. In addition to the risk of further attacks, there is also the risk of merchant vessels or commercial aircraft being misidentified and fired upon by the numerous military actors in the region.

Ultimately, for companies operating, or vessels heading into the region, it does not matter if it is an Iranian, Houthi, American or Saudi mine that results in damage to your vessel, the outcome would be the same. The latest attack, coupled with the incident in Fujairah, have highlighted the vulnerability of merchant vessels as well as the need for caution by all stakeholders. The attacks targeted a wide variety of vessels, did not target any flag or owner, with the only consistency being that all the vessels were tankers, and not bulk carriers. Additionally, five of the six ships originated from, or were anchored at, UAE ports.

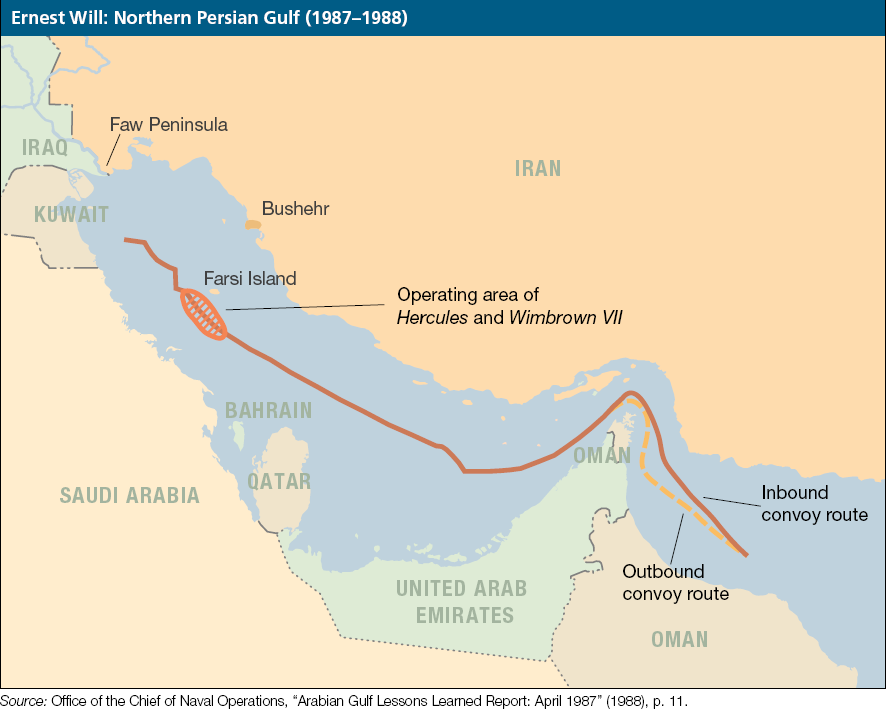

Going forward, it is likely that naval forces, such as the Royal Navy, may consider escorting merchant vessels in a convoy system. A similar tactic was used in the late 1980s when the American military conducted Operation Earnest Will, which involved naval vessels (as well as air force assets) escorting merchant vessels in a convoy system during the “Tanker War” phase of the Iran-Iraq War.

The Tanker War

During the 1980s Iran and Iraq were locked in a protracted conflict, both sides targeted each other’s energy vessels, or tankers, in the Gulf of Persia and the Strait of Hormuz. Iraq largely used fighter aircraft, while the Iranians became more inventive with their methods of attacks; including speedboats, sea mines, anti-ship cruise missiles and traditional naval gunfire, among others. The United States intervened after Iran demonstrated the capability to attack any vessel, Iraqi or other, passing through the Strait of Hormuz. The American military implemented Operation Earnest Will to escort vessels through the Gulf. In total, 340 ships were attacked, and more than 30 million tonnes of shipping damaged in the Gulf between 1981 and 1987. It also caused over 400 seaman deaths.

American, British and Saudi naval assets may look to implement a similar plan; especially should another attack occur. The escorting would at least protect merchant traffic while investigations are ongoing, greatly increasing the risk of detection and/or capture in any further attacks by the perpetrators; should they be intent on continuing to target merchant traffic.

However, this move would be politically sensitive, and, vitally, could result in an additional escalation risk. Iranian naval assets may decide to shadow all naval assets should they come in close proximity to their waters. This could result in an event similar to the 23 March 2007 seizure of Royal Navy personnel from HMS Cornwall by Iranian Revolutionary Guards. The personnel were searching a merchant vessel off the coast of Iraq at the time of the incident.

Other measures, which can be implemented in a shorter time frame, are also possible: ships could be mandated to operate in the region with all doors and hatches closed, to help increase the watertight integrity of their hulls and to help reduce damage from possible blasts. Making sure that crew sleep in areas of the ship above the waterline would also help reduce the risk of injury or death in the event of an attack. Increase the number of crew members on watch, possibly posting additional members on watch on the bridge wings.

The Strait of Hormuz

The energy rich Persian Gulf has naturally emerged as a vital trading hub as large numbers of vessels export oil and gas from the region. The Strait of Hormuz is 39km (21nm) wide at its narrowest. A third of global crude oil exports are transported via ships that pass through the strait; making it the most important shipping lane for the global oil trade. Additionally, all of Qatar’s LNG passes through the strait. If the Strait were to be cut off or the free flow of vessels disrupted, even for a brief period, it would have serious ramifications on the global energy industry; likely causing prices to rocket.

It is also vital that ship owner and vessel masters stay aware of the latest developments. Keeping in touch with the UKMTO and other maritime operators in the region is vital. Keeping up to date with the news where possible can aid in avoiding unnecessary risks.

Additionally, many of the measures developed to harden ships against pirates off the coast of Somalia in the Best Management Practices to Deter Piracy and Enhance Maritime Security in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea (BMP5) can be employed in the Persian Gulf, whilst transiting the Strait of Hormuz and in the Gulf of Oman. Adhering to the advice given regarding anti-ship missiles and mines can help protect ships and crew prior to, during and after an attack.

Finally, the Strait of Hormuz is among the most vital choke points on earth. With further attacks likely, it will only be a matter of time before a serious injury, death or a vessel is sunk, which will have serious economic, environmental and political ramifications.

Updated Advice

- All vessels and companies operating in the area should continue employing the highest degree of caution in the coming weeks and months.

- Thus far, the attacks have occurred at night, consider transiting the Straits of Hormuz during the daylight hours. However, as there has only been two incidents at this time, attacks may begin to occur during the daylight hours; remain flexible.

- Limiting the time spent at anchor in the region is advised.

- Keep an appropriate distance from Iranian waters for the foreseeable future.

- Consider operating at the maximum possible speed whilst remaining safe from a navigational point of view.

- Continually operate a gentle side to side motion with the vessel’s rudder in order to make the ship weave; making approaching the vessel more difficult.

- Equip the crew with night vision which may help in identifying suspicious activity at night.

- Employ additional personnel on watches; including on the bridge wings and at different areas of the ship whilst at anchor.

- Employ searchlights at the first sign of suspicion; thus far the attacks have wanted to remain clandestine in their activities. Illuminating them and possibly using loudspeakers may deter attacks.

- It is strongly advised that you do not employ flairs or emergency rockets; the attackers may return fire.

- Companies and vessels should remain in contact with the UKMTO in Dubai and the US Navy in Bahrain; ensuring that they receive regular updates from both.

- Strictly adhere to any official maritime notices as well as any official orders issued by countries in the region.

- Report all suspicious maritime activity immediately.

- Remain in contact with stakeholders and company headquarters.

- Continue to monitor all Solace and media updates for the latest information.

- Finally, as all previous attacks have only caused superficial damage, remain calm and follow procedures in place.