2019: A Year of Unrest Powered by Social Media

20 December 2019

A Year of Unrest

Social unrest has been an integral part of human history and has contributed to fuelling changes that have radically shaped modern societies. From the Civil Rights Movement to the Arab Spring, strong messages and powerful leaders, such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, have encouraged people from all nations to take to the street and ask for reform, even when confronted with violent repression.

However, the past decade has seen an emergence of a radically new type of social movements, greatly shaped by the increasingly global and interconnected civil society. Powered by the ability to share and receive information almost in real-time, people have surpassed physical barriers and connected across their country, societal class and sectarian group to create grassroots movements and encourage dissent.

The demonstrations the world has witnessed in the past year in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe and Latin America share this important characteristic. They are fuelled by messages and principles fostered on social media platforms that instantly spread, not only within their own society but worldwide. They do not rely on a leader to guide them, but on viral content and powerful symbols that create a sense of collective identity, which has the potential to inspire similar groups across the globe.

Governments and security establishments have actively engaged these movements on social media, often resulting in battles of conflicting narratives or, in worse cases, attempts to suffocate demonstrations by shutting down internet services. In this report, we examine these scenarios and provide an overview of the role social media has played in mass protests this year.

Powered by Social Media

Social media platforms have been widely used in protests worldwide as a communication and organisation tool for over a decade. Without it, the 2011 Arab Spring, one of the largest waves of unrest in recent history, would never have happened.

At the same time, the growth of crowd-sourced information and reporting has contributed to the spread of misinformation, as well as state surveillance. Governments have grown aware of the power of a global network and narratives, particularly as platforms like twitter are increasingly hosting debates over policy and ethics. In countries like China, North Korea and Iran, western social media platforms are permanently banned, while the practice of imposing internet blockades during periods of social unrest is becoming more common.

In the current Information Age, with the number of internet users surpassing 3.5 billion people, there are countless online spaces used to share knowledge, concerns and know-how. Social media has enabled dialogue among activists both domestically and worldwide, lending an international space to local issues and giving a new definition of collective consciousness and responsibility.

This year alone, we have witnessed cases of internet services being shut down, even pre-emptively, before the implementation of controversial legislation with the expressed purpose to prevent movements from organising effectively and to deny real-time media access. Examples range from Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir, to Iran, to Venezuela.

Social media has become the medium through which people make sense of most aspects of the state and its activities and, in turn, hold it accountable. Conversely, it can be used by the state to better monitor, restrict, and deter social movements that it considers a threat.

The real-time nature of live streaming and platforms like twitter is increasingly being used to demonstrate transparency in a group’s actions and the integrity of its narrative. This is evident in cases like Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement or Extinction Rebellion, largely leaderless movements that encourage open communication through social media, spontaneous gathering and the promotion of their political narrative in English. This enables global exposure and engagement, allowing the movement to spread across different communities, neighbouring states or even continents.

In Hong Kong’s case, social media reporting has largely become synonymous with free press and it is used to document cases of police brutality. The demonstrations are also coordinated through encrypted messaging mobile applications like Telegram, where participants can vote on open and anonymous polls to make collective decisions on the movement’s direction.

Several live streams broadcast at all times, allowing viewers across the world to gain direct insight into the rallies, sit-ins and demonstrations. This, in turn, lets the viewer gauge the levels of violence used by either the demonstrators or the security forces, the extent and of the disruption created, ultimately leading to a more direct and personal engagement with the movements.

Decentralisation is integral to the longevity of these civil unrest movements, as international support or condemnation plays a key role in sustaining or damaging their momentum over time. The daily involvement of the global community deters security forces from exercising excessive violence, providing an additional layer of accountability to the governing authorities.

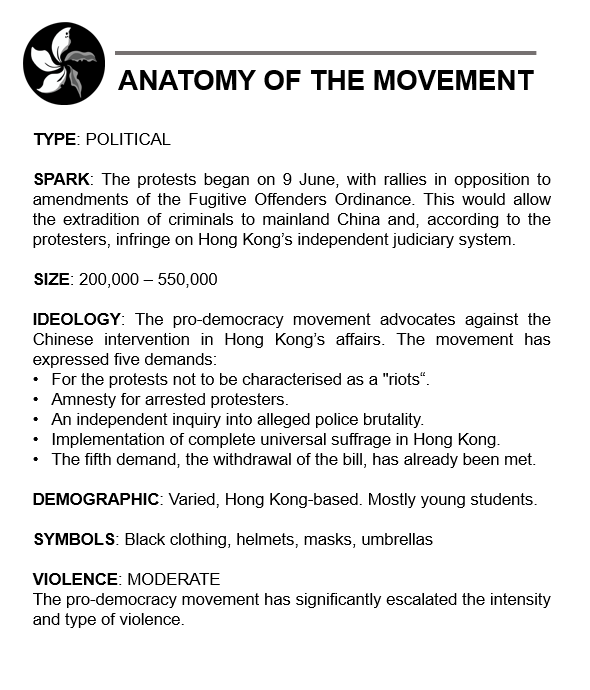

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is now well into its sixth consecutive month of demonstrations, showing little sign of de-escalation in what has become increasingly an ideological battle for the future of the city and its citizens.

What started as a series of largely peaceful rallies against a highly controversial piece of legislation rapidly transformed into a full-fledged pro-democracy movement, which carries the accusation of Beijing’s excessive interference into Hong Kong’s affairs, fundamentally breaching its already limited sovereignty. This fed into the narrative of a fight for freedom promoted by the demonstrators, fuelling tensions with both the Hong Kong and Beijing authorities, and radicalising the movement and attempts to restore order.

The escalation in violence started relatively soon after the initial rallies, mostly following a tit-for-tat format between the demonstrators and the police. At least three distinct phases can be identified in the evolution of the movement and the escalation of violence:

PHASE 1 Represents the initial phase of confrontation, which remained largely peaceful from either faction. It mostly consisted of large rallies in the area surrounding the Hong Kong Legislative Council and Victoria Park. Localised clashes took place between the demonstrators and the police, with the former throwing bricks and bottles and often charging at security barricades, while the latter employed suppression tactics including tear gas, pepper spray and rubber bullets.

PHASE 2 Entails both an ideological shift and a heightened intensity in the confrontation, whose start can be traced back at the beginning of July when the protesters stormed and vandalised the Legislative Council despite the announcement by government officials that the bill was temporarily suspended. This represents a turning point in violent exchanges between the police and the demonstrators, as well as the establishment of an ideology that goes beyond the abolishment of the extradition law but structured around the five demands.

PHASE 3 Started in October and was fuelled by the first serious injuries and deaths. On 1 October, during the commemorations of the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, violent clashes in Hong Kong resulted in an Indonesian reporter being shot in one eye and blinded. This was closely followed by an escalation in violence that led to the police using live ammunition, the pro-democracy movement to increasingly creating offensive weapons, and ultimately culminating in the PolyU siege. Acts of violence against pro-Beijing businesses or supporters continue to grow, while the security forces and officials are also becoming more aggressive. Controversial legislation, such as the mask ban, is being implemented by the Hong Kong authorities, while any concession to the protester’s demands has so far been limited and surrounded by contention.

Extinction Rebellion

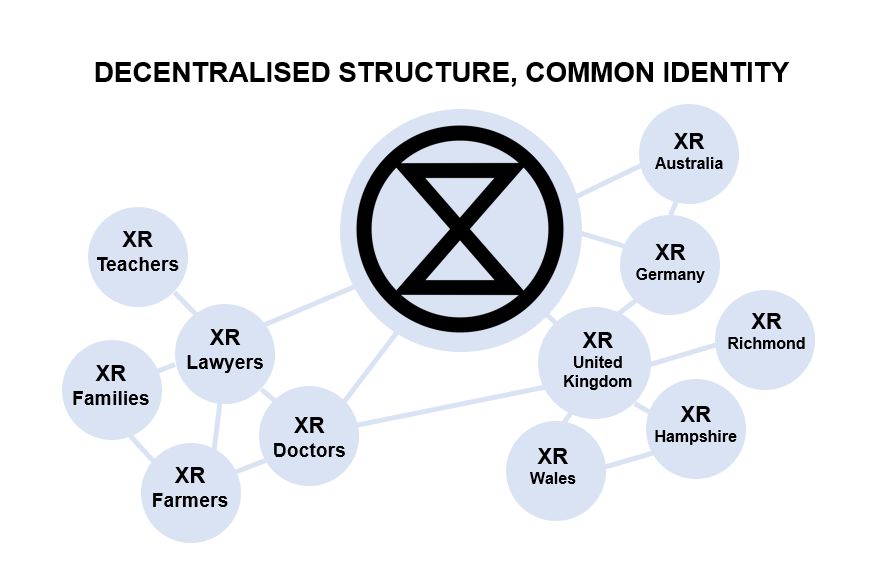

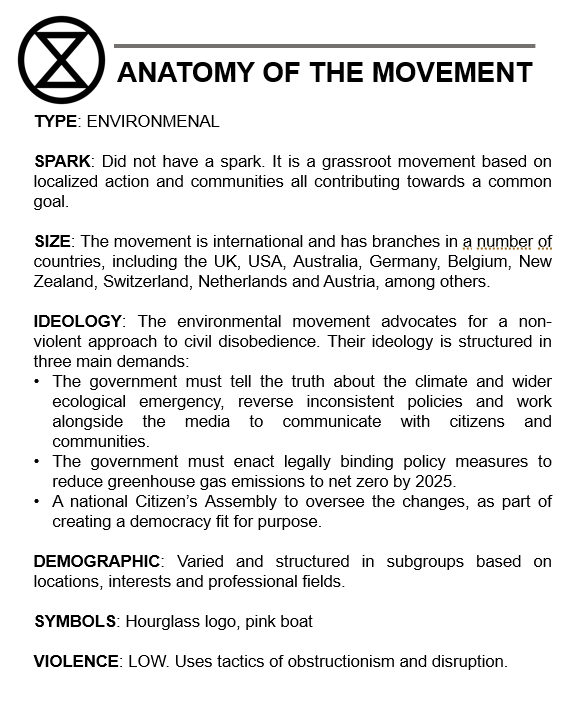

The Extinction Rebellion (XR) is a socio-political protest movement centred around environmental issues that was created in the UK in May 2018. It employs non-violent action and civil disobedience methods to emphasise its message of climate change and tragic loss of biodiversity on Earth. Whilst XR affiliated groups have since then emerged worldwide, its largest and most disruptive events take place in the UK.

XR came to prominence in November 2018 when, in what was called “Rebellion Day”, thousands of people took part in coordinated action to block the five main bridges over the River Thames in London, causing massive disruption throughout the city. Since then, the group has grown larger, carrying out increasingly complex and wider disruptive actions, which are announced in advance through most social media platforms.

The movement’s ability to expand across borders and have such a capillary presence in local communities is grounded in their highly decentralised nature, where virtually any sub-group can be part of Extinction Rebellion as long as it adheres to its guiding principles.

While fitting with the movement’s narrative of civic ownership and agency over stopping environmental degradation, its network of social media-based groups allowed it to build a sense of identity in those individuals that, although sharing the concerns, would have been unsure on how to take action.

Extinction Rebellion subgroups are geographically specific, with community-based cells that are encouraged to reflect and act upon on their unique concerns, allowing it to quickly spread across different countries. Other types of sub-division are specific to professional or social condition, with “affinity groups” such as XR Doctors or XR Teachers, where the members discuss ways to have a positive impact in their respective fields of expertise.

The way the groups uses technology for planning and communication purposes, with a myriad of subgroups organising and cascading information to each other on publicly accessible instant-messaging applications greatly resembles the techniques used in Hong Kong. While this guarantees a high degree of flexibility to the organisation, it also provides the same level of access to information to the general public, government and law enforcement. The choice for transparency allows Extinction Rebellion to be publicly held accountable, as all its actions are detailed and broadcasted, together with those of the police and law enforcement.

Their strategy seems to be working. While XR remains a controversial movement, their protests have been a massive success. There has been a surge in public concern across the United Kingdom. The climate emergency is now established in the top five most important issues facing the UK today. The government has legislated for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 with other parties moving towards much more ambitious targets.

Latin America and the Viral Domino Effect

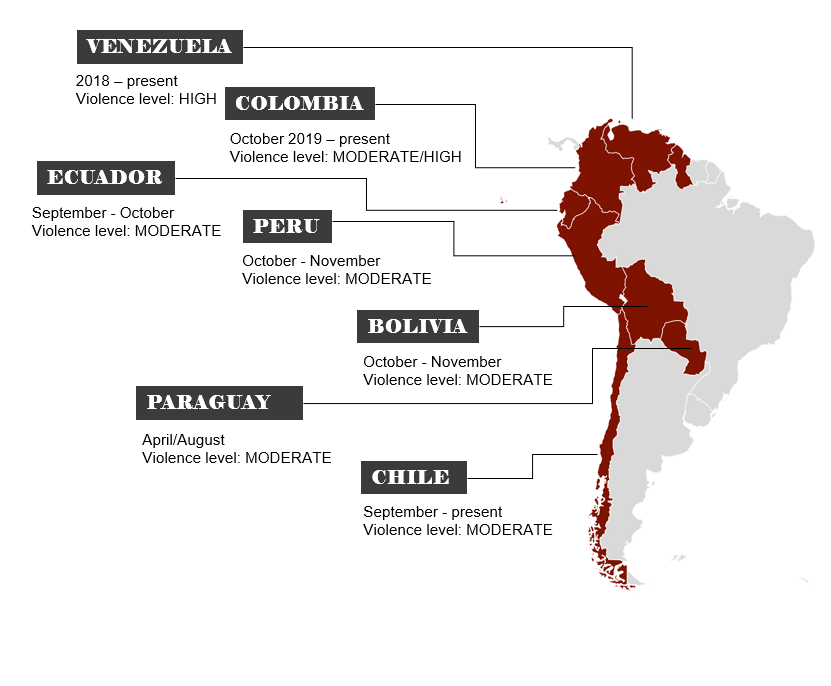

Civil unrest has been a truly global phenomenon this year and has largely affected several states in Latin America, leading to the resignation of many heads of state. The demonstrations, now affecting virtually every South American state bar Argentina and Brazil, seem to have radiated through the continent and threaten to spread chaos to the entirety of South America, further exacerbating the endemic issues of economic stagnation, violence and mass migration.

Latin America has a rich history of civil unrest and the recent economic slowdown, rise in inflation and unemployment, as well as widespread corruption represent the main motivators for the demonstrations. While the demonstrations’ initial triggers were relatively varied from country to country, ranging from a hike in metro fares in Chile to a revolt against Evo Moral’s attempt to hold on to power in Bolivia, the underlying theme remains the general dissatisfaction with the government’s performance.

The increased access to real-time and crowd-source information has caused a positive growth in public awareness and political participation in relation to both the government’s actions and the wider regional context, which played a central role in allowing the unrest to spread from state to state. These, however, only occasionally follow political or ethnic lines, being instead structured as a wider, often leaderless, movement of civil disobedience reliant on social media.

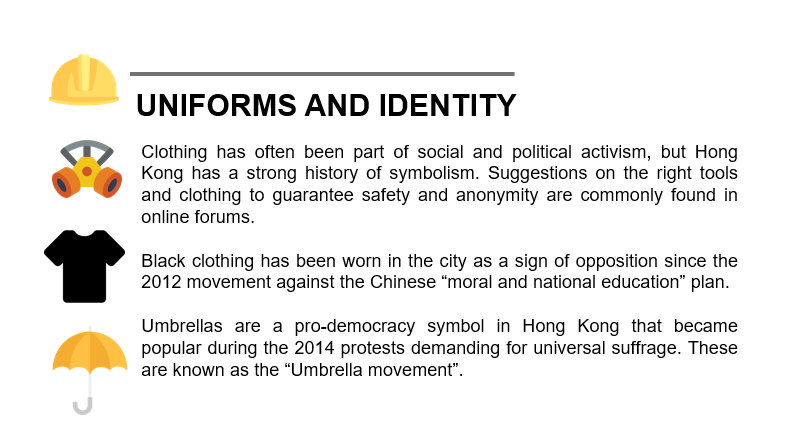

Leaderless and social media powered movements are becoming increasingly common throughout the world, often replacing the catalytic power of the charismatic leader with viral content online, which quickly becomes a symbol of collective identity and gives momentum to the demonstrations. While this is evident in instances like Hong Kong or Extinction Rebellion, it is present in almost every other demonstration worldwide. The almost universal use of hashtags, as well as the creation of viral icons, are some of the tools used to mobilise crowds and maintain the public’s commitment to the narrative.

In Latin America, for instance, the concept of protests through the cacerolazo, producing sound by banging household appliances has been growing as a method of non-violent civil disobedience. This has quickly been adopted by the different movements across the continent and it was combined with local icons, memes and slangs.

However, these popular narratives have often been contested by governing authorities, which have accused prominent social media platforms, such as Facebook or Twitter, of being instruments of western imperialism used to undermine and destabilise the state. Internet blockades have been implemented in several occasions with the stated aim of preventing the spread of misinformation, sparking concern over the government’s ability to curtail freedom of speech and reporting, as well as to hide violence perpetrated by security forces.

In Venezuela, a prolonged political and economic crisis has resulted in a deterioration of the country’s security and economic situation to the point that a humanitarian disaster has occurred.

In Colombia, during November, protests took to the streets in the country following growing discontent with President Ivan Duque ‘s government.

In Ecuador, President Lenin Moreno withdrew the fuel subsidy that had been in place since the 1970s due to an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The resulting rapid increase in the price of fuel saw mass protests that paralysed the country in October.

In Peru, President Martin Vizcarra dissolved congress in an attempt to force new parliamentary elections. These actions resulted in several demonstrations around the country, including one that blocked access to a copper mine and caused production to cease.

Bolivia also saw a massive wave of demonstrations following the alleged doctoring of election results by the then incumbent President Morales. The unrest reached such a level that foreign government began advising against all but essential travel.

Paraguay has been experiencing unrest following a secret hydropower deal with Brazil, which those in-country believe is detrimental to the smaller country. The unpopularity of the governments has also resulted in the commencement of impeachment proceeding.

Chile, considered one of the most economically developed countries in South America with the highest human development index and one of the highest per capita GDPs in the region, has also seen its biggest wave of civil unrest since its re-democratisation in 1990.

Can The Government Fight Back?

Algeria

Since February, Algerians have taken to the streets to protest against the country’s political and military elite. What started as a rally against the announcement of the electoral candidacy of longstanding President Abdelaziz Bouteflika quickly escalated into his resignation and uncertainty for the future of the country.

Much of Algeria’s 41 million population is under 25 and most know no other leader than Bouteflika. Those who do, remember the war that proceeded him. As such, until recently, many Algerians have been apathetic toward politics, choosing peace and stability over political reform. The country’s political elite has fuelled this, highlighting the devastation in neighbouring Libya as the only possible outcome of revolutionary efforts.

However, the announcement that Bouteflika was attempting to retain his presidency after being absent from the political scene for six years triggered public outrage. The first major demonstration took place on 16 February 2019 in Kherrata, at the eastern end of the wilaya of Bejaia. Unrest then continued to escalate despite all attempts to appease the crowd, including the withdrawal of Bouteflika from public office.

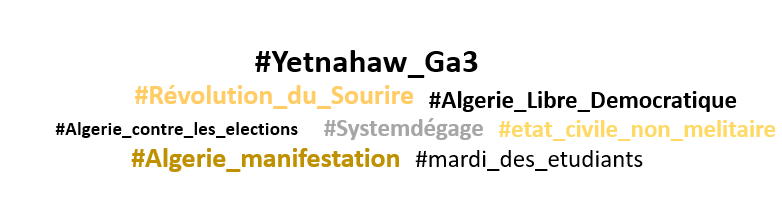

The slogan of the unrest, Yetnahaw Gaa (They All Should Go), mirrored in the current protests in Lebanon, provided clear evidence of the dissatisfaction of the Algerian population with the ruling elite as a whole, often referred to as “le pouvoir”, “the power”.

Yetnahaw Gaa, (يتنحاو ڨاع) in Algerian Arabic, is often written Yetnahaw ga3!, for the sole purpose of social media. The phrase was coined after a video that went viral on social media and the phrasing quickly was posted with all content related to the protests.

However, the protesters have not had a monopoly of the internet. An information battle is ongoing on the country’s social media, with pro-government accounts that continuously spread messages in support of the ruling elite, attempting to build an equally successful counter-narrative. These accounts have been termed trolls by some, or “electronic flies” by others.

In response, anti-government groups and mainstream media have reported on the authenticity of the “flies” and the information they release, running widespread verification campaigns. Generally, the fake accounts are easy to spot, with less than 100 friends or followers and their creation dating sometime after the start of the protest. These accounts then comment on numerous message boards and posts in “an effort to try and swerve the debate”.

While these accounts are overwhelmingly fake, what is less clear is who is running them. It remains unclear whether these are part of a coordinated government campaign, an independent initiative, or run by an organisation. Some protesters have expressed their concerns over the interference of foreign powers, similar to the Russian efforts to influence the US 2016 election.

The question is crucial, as most of Algeria’s population gets its news from Facebook. This war over information means that the narrative of any civil movement or key event has the potential to be shaped by a well-concerted cyber effort to create “fake news”. Despite the efforts by civil society groups to debunk their posts, opposing narratives continue to exist, many even stating that demonstrations are no longer needed and that Algeria is now thriving.

Iran

The latest protests in Iran represent a strong reminder of what can happen when a country completely shuts down communication. In November 2019, as civil unrest erupted due to a cut in fuel subsidies, the Iranian government deliberately interrupted the internet service before cracking down on the demonstrators.

According to a report by Amnesty International, at least 304 people were killed, with security forces described as firing on protesters that “did not pose any imminent risk”. Thousands were also arbitrarily detained.

In 2018, it was estimated that Iran had an Internet penetration rate of between 64 to 69 percent out of a population of about 82 million. Despite this, Tehran is heavily associated with internet controls, with an average of 27 percent of internet sites reportedly blocked in the country, including around 50 percent of the top 500 globally visited sites. This is coupled with semi-state-run media providers, many of whom spread disinformation or government propaganda.

When the Green Revolution took place in the country ten years ago, around 1 million Iranians had smartphones. Today, the number is more than 48 million. The most popular app on these 48million+ smartphones is Telegram, which is used to buy clothes, find doctors and, during periods of unrest, as a key source of information about the protests. This practice is not new, and the diffusion of information is now almost instant in Iran.

As such, despite state restrictions, information travels fast, which is why, after the breakout of the unrest, the internet was simply shut down. Starting from 17 November 2019, internet traffic in the country dropped to about 5 percent of normal levels.

Technology is playing a central role in allowing people to organise protests and share information with each other. This was most evident in 2017-18 when Iranians across the country watched as protests began in Mashhad on 28 December 2017.

Within a two-week period, the unrest had spread to over 140 cities as demonstrators took to the streets, far away from Mashhad. The vast majority of these protests were organised on social media messaging apps.

As a result of these protests, the Iranian Minister of Interior Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli stated that “violence and fear” were being caused by the “improper” use of social media. This was followed by a restriction on the use of social media outlets while the Iranian state and semi-state media were also quickly banned from reporting on the protests. These media outlets instead ran a rhetoric of the protesters showing “anti-social” behaviour.

In the most recent protests, the Iranian government did not even attempt to restrict social media, instead, Tehran simply cut off internet access almost completely.

The move is drastic and is not taken lightly, it shows the escalation in both the government response to the unrest, which is also evidenced in the high number of fatalities, the most in a single spell of unrest since the Islamic Revolution between 1978-79.

The shutting down of the internet is a popular tactic for countries looking to quell unrest, in the past 12 months there have been more than 11 shutdowns in 29 countries. Ethiopia, Sudan, Kazakhstan and Zimbabwe all shutting down internet access; however, India, a nominal democracy, has also employed the tactic in an effort to suppress protests.

Despite these attempts, as Egypt found out during the 2011 Arab Spring, shutting down internet and telephone services does not suppress already ongoing protests and, in many cases, it makes them worse. Instead, in shutting down the internet quickly, the protests failed to gather momentum like in Egypt or Iraq.

With less people on the street and in the darkness when social media is turned off, protesters can be killed, injured and detained, without the public, and indeed the wider world audience, watching.

Conclusion

The importance of social media in the recent protests cannot be understated. The governments of India, Iran, Sudan all would have avoided abruptly shutting down their internet services if they did not believe in the impact of social media amplifying the protester’s message. Without the ability to communicate online, protesters are forced to resort to word-of-mouth tactics, limiting reach and spread, and preventing them from broadcasting to the international community.

Social media makes it easy for a decentralized, unorganised protest movement to gather, to spread its message, to organise. Whereas in the past leaders of civil rights movements have been high profile, well known orators and symbols of their movements, Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela all prominent examples, now the leaders are not known, or, in some cases, none exist.

Instead, social media has allowed movements to grow almost organically, fitting the mood of the public, in what could be a first attempt to truly democratise public disobedience. The example of Algeria shows that, regardless of the resistance that the political elite put up, these movements can gain significant momentum even without resorting to violence.

However, even fighting these movements with their same tools has often frustrated government efforts. In Hong Kong, Pro-Beijing activists and residents routinely post on social media condemning the unrest, in Algeria accounts on Facebook and Twitter, believed to be fake, attempt to “swerve” the online debate and undermine the protest movement. In Iran and India, more extreme measures were taken, such as the complete shutdown of internet services.

In addition to facilitating communication and organisation, social media live streams allow the protesters to broadcast the events as they unfold, creating a degree of accountability for police violence in the court of the public and international eyes. This can be a powerful tool for protesters, as videos and images can go viral in the global online space, such as the picture of the woman on a vehicle in Khartoum, the photos of the one-eyed journalist in Hong Kong or the XR boat in London.

While these symbols are great tools to sustain the momentum of the protest and create a sense of shared identity, they also attract international attention. This has led to concrete legislative initiatives, such as the US bill in support of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong , the UN has accused the Chilean security forces of human rights abuses and condemnation from other protesters and government authorities were levelled at the French yellow vest protesters after videos emerged of anti-Semitic abuse by a small section of its members.

This makes social media not only a tool for communication but also one to hold those taking part, both the protesters and authorities, accountable for their actions.

As we enter 2020, these protests are only going to continue, and the importance of social media is only going to grow. Protest groups are already moving to more secure communication methods, Signal or Telegram, trying to preserve the anonymity and privacy of their members. Going forward, however, they will need to be wary of the possibility that authorities can manipulate or prevent access to these platforms. Social media has become a key tool for freedom of speech, and protest movements, how governments react to this will shape mass protests in the coming decade.

Learn more: What are the hotspots for political instability 2023/24?

Solace Global: Your Trusted Partner for Secure Business Travel

At Solace Global, we understand that the well-being of your employees is paramount, especially when it comes to business travel. Our intelligence-driven approach allows us to identify potential threats and vulnerabilities, empowering your organisation to proactively navigate complex environments.

Global Intelligence

Arm yourself with the knowledge to avoid a potential threat from turning into a crisis. Intelligence advisories give you tailored reports to anticipate possible disruptions, mitigate risk and help you make well-informed decisions, faster.

Security Assurance

From tailored risk assessments and executive protection to crisis management, our security solutions guarantee the safety of your business travellers, addressing potential threats and providing swift responses.

Integrated Solutions

Recognising the unique needs of your organisation, our solutions are customised to ensure optimal protection.