Iran Protests: Impact on Regional Security

October 2022

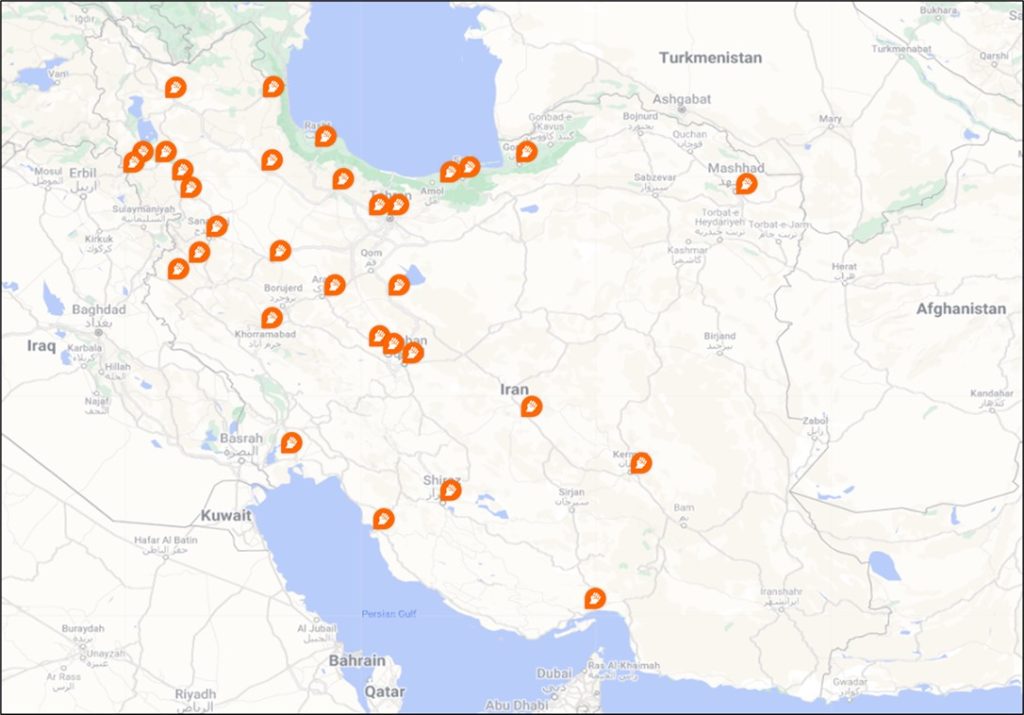

A diverse coalition of women’s rights activists, proponents of secularism, labour workers, and other groups with grievances against the Iranian government have begun a widespread series of protests across the length and breadth of Iran. Sparked by the death of a young Iranian woman at the hands of the security services, the protests have attracted support across large swathes of Iranian society, placing pressure on the Iranian government and limiting its ability to respond in force.

Examination of the impact of protests in Iran

This report highlights the short and medium term risks of further escalation due to the rapid spread of the protest movement, its ability to sustain itself over several weeks, and the limited options available to the Iranian government to quell dissent. There is an outstanding risk of escalation at the regional level, particularly in Iraq, and spill-over effects across the Middle East and Central Asia in the form of unrest elsewhere cannot be ruled out. It is likely that the protests will persist over the short-term, placing greater pressure on the Iranian government to outline a more effective strategy for managing dissent which current signalling, mixed with lessons taken from previous uprisings, is likely to result in further violence and disorder.

Background and Current Situation

On 16 September 2022, 22-year-old Iranian woman Mahsa Amini was allegedly killed by members of the Guidance Patrol, the state-backed religious police who had reportedly arrested Amini for wearing a hijab in an incorrect manner. Official police reports indicated that Amini had passed away as a result of a heart attack; however, eyewitness reports suggested that the Guidance Police had beaten Amini in a display of police brutality that shocked large segments of the Iranian population.

A group of largely female protesters gathered near the Kasra Hospital in Tehran in the hours immediately following Amini’s death. These protesters called for justice against the alleged killers of Amini and directly criticised the Iranian government, including the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Further protests were later documented in Argentina Square in Tehran, with demonstrators gathering to oppose Iranian laws which make the wearing of a hijab compulsory for women. These demonstrations were met by repressive action on the part of the Iranian security services, and videos allegedly taken from the event and shared on social media indicated that several protesters were subject to detainment and arrest.

Large-scale demonstrations erupted in the Iranian Kurdistan towns of Saqqez and Sanandaj on 17 September, the former of which was the hometown of Mahsa Amini and the site of her funeral. These demonstrations led to similar outbreaks of unrest in locations such as Tehran and Mashhad on 18 September, which led to calls for a nationwide strike from Iranian-Kurdish political actors on 19 September. The response of Iranian security personnel intensified following these developments. An internet blackout was introduced in central Tehran and fatalities were reported amongst the protesters.

Public anger with the death of Amini, including the institutions within the Iranian regime which permitted such an event, and the response of the Iranian security forces prompted a major upswell in civil unrest that spread throughout Iran from 20 September and onwards. Protests were recorded in the majority of Iran’s 31 national provinces, and further fatalities were documented as security personnel utilised live ammunition against protesters in various cities and towns across Iran. Internet blackouts were extended nationwide on 21 September, and the use of violence as a tactic deployed by protesters began to spread. Consequently, significant disruption to social and economic activity was reported across Iran, with educational institutions, businesses, and other organisations disrupted by public demonstrations and the destruction of property in the surrounding area.

Response from Iranian Security Services

The response of the Iranian security services has grown more repressive with each escalation. On 30 September, Iranian police opened fire on civilians in the city of Zahedan, Sistan and Baluchestan Province, killing at least 40 people. Riot police have been deployed to many of the focal points of the unrest, particularly in Tehran, with the intention of controlling dissent and preventing further disruption. The discovery of the body of Nika Shakarami, a 16-year-old schoolgirl who disappeared during the protests, prompted further anger amongst the population, triggering protests at schools throughout Iran.

Demonstrations continued into October, and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has explicitly labelled the protesters and wider civil movement as a “riot” backed by foreign collaborators. Attempts made by both the Supreme Leader and President Ebrahim Raisi to calm demonstrators through appeals to unity and the importance of Iran’s various minority ethnic groups to Iran as a whole have failed to quell public anger.

Support for Iranian women demonstrating against oppressive practices and for opposition groups seeking to weaken support for the Iranian regime has spread to wide segments of Iranian society in the weeks following the initial outbreak of unrest. Hacktivist groups have sought to utilise the unrest to target Iranian state media assets, and as of 10 October, petrochemical workers have begun to engage in collaborative activity in support of the nationwide protest movement. Petrochemical facilities in Bushehr and Damavand are the focal points of solidarity-inspired strike activity; a shift in the nature of the unrest which is likely to attract significant attention from the Iranian government due to the petroleum industry’s vital role in the national economy.

As of 17 October, the protests in Iran have entered their fifth week and have not displayed any signs of slowing, rather appearing to gain traction amongst more sections of the Iranian public. Indeed, anti-regime organisations and social media accounts are increasingly calling for the overthrow of the Iranian regime. Iranian security personnel continue to pursue aggressive measures in response to demonstrators, conducting arbitrary arrests – including of foreign nationals – and deploying considerable force to disperse and control crowds of demonstrators. These measures are likely to persist, and protest activity should also be anticipated to continue in the coming weeks

Impact on Iranian domestic security

Iran’s protests over the death of Amini, the relationship between religion and the state, and the nature of the Iranian regime have attracted widespread support across a diverse cross-section of Iranian society. Unrest has spread across Iran’s ethnic groups, such as the Kurds, Azeri, Persians, Arabs, and Baluchi, whilst also spreading across religious and socioeconomic groups too. The sheer speed at which the protests have reverberated from Tehran and Kurdish territory across the wider geography of Iran also indicates the extent of public anger and discontent towards the regime. It is unlikely that the protests, which have already entered their fifth week of activity, will subside in the short term. Indeed, it remains realistically possible that a notable expansion of protest activity could exceed the ability of the Iranian security apparatus to respond effectively.

It is likely that the Iranian regime will continue to crack down forcefully on protesters as unrest continues. Iranian security personnel have displayed a willingness to use violent and lethal force against demonstrators both in the current wave of unrest and in previous instances of large-scale protests in Iran. In November 2019, a pro-democracy and anti-fuel inflation political movement was quelled by the authorities via lethal methods, resulting in the deaths of approximately 1,500 Iranians in an event known as “Bloody November”. The Iranian regime has not resorted to such an overwhelming display of force against the current wave of protests, likely due to their geographic spread and the diversity of supporters, but incidents of mass violence against crowds at protests have occurred on a smaller scale than the Bloody November event.

The grassroots nature of the movement complicates the response of the Iranian authorities. Attempts to block internet access and interfere with the coordination of protests across social media channels reflect this reality and are likely to continue for the duration of the protests. Indeed, localised internet outages were reported during a riot at the Evin prison on 15 October. The control of information is a key feature of the Iranian regime’s ability to control and subjugate the Iranian public; a factor that hacktivist networks of both domestic and foreign origin are likely to exploit further to disrupt the Iranian government’s control over the security situation in-country. Disinformation spread by both the Iranian regime and protesters may also result in further escalations, as misattributed videos of police brutality or other controversial incidents can trigger outbreaks of misdirected violence during volatile periods marked by high tension amongst the populace.

It is the diversity and wide geographical spread of the current protests which compounds upon the complexities of managing a grassroot movement of unrest faced by the Iranian government. Previous outbreaks of unrest have been localised in specific regions or cities, allowing the Iranian security apparatus to pivot tactically to unrest as and when it appeared. The current protests are occurring on two broad fronts: in peripheral regions with a history of discontent towards the Iranian government, and in major population centres. The Iranian authorities have typically relied upon a small cadre of ideologically motivated and highly trained security personnel for disrupting any internal unrest, with these forces mobilised and deployed across the country but typically to the border provinces where unrest is more common. The geographical scope of the current protest movement is likely to place considerable strain on these forces to control larger-scale demonstrations occurring simultaneously across the country, and any attempt by demonstrators to coordinate protest activity across the country is almost certain to compound this issue. Initial indications of coordination by civil society groups have already begun to emerge, such as a statement published by the Free Union of Iranian Workers on 12 October which called for labour strikes across Iran in conjunction with the protests. In the short term, the domestic security situation in Iran is likely to remain volatile, largely due to the Iranian regime’s continued insistence on dismissing the demands of protesters. Meetings between Iranian and Kurdish officials have been documented, including those involving senior officials such as Interior Minister Ahmad Vahidi, but comments from both the Supreme Leader and President Ebrahim Raisi remain dismissive of the protests and continue to highlight the alleged involvement of foreign actors. The involvement of economically critical industries and labour organisations in the protest movement is likely to place greater pressure on the Iranian regime to adjust its messaging if sustained over the medium-term, but crackdowns on civilian protesters within cities and in restive regions are likely to continue in the short-term as the Iranian security establishment continues to direct messages to actors within its own circle.

The response of the Iranian regime will greatly impact the domestic security situation over the medium-term. Any pivot towards creating avenues for public dissatisfaction and responsiveness to protester demands creates a realistic possibility of diffusion of the worst excesses of the unrest, potentially freeing state capacity to exercise force against a hypothetically smaller, more insistent core of protesters. In contrast, an inability to create such avenues for responding to public discontent is more likely to engineer a scenario whereby the regime will be forced to either wait for fatigue to set in amongst protesters or pivot towards a large-scale crackdown precipitating a far more violent and unstable security environment.

Impact on regional security

As one of the Middle East and Central Asia’s most influential powers, significant domestic developments within Iran hold the potential to impact wider regional stability and security. Any major deterioration in the Iranian security environment can create the potential for spill over effects beyond Iran’s borders, or for a reassessment of the priorities of the Iranian state as it shifts towards maintaining a hold on domestic power. While the protest movement has not prompted a major reallocation of Iranian resources at this time, spill-over effects have been observed, and shifts in the behaviour of neighbouring or regional powers towards Iran have also been documented.

Iraq is the country most likely to experience significant repercussions as a result of the shift within Iran’s domestic political environment. Iran’s shared border with Iraq stretches through large swathes of Kurdish-majority territory on both sides. In Iran, Kurdish towns and cities have reported some of the most intense displays of unrest in recent weeks, motivated by the Kurdish heritage of Mahsa Amini and long-standing disagreements between the Kurdish population and the Iranian regime. Opposition groups residing within Iranian Kurdistan have voiced support for demonstrators and have previously been subjected to attacks from the Iranian regime, with the Iranian state labelling such groups as separatist movements. In the current juncture, these groups have also been identified by the Iranian regime as part of the coalition of foreign actors allegedly responsible for provoking unrest within Iran.

Potential disruption in Iraq

Protests within the vicinity of border checkpoints between Iran and Iraq have been documented, and there is an underlying risk that Iran’s actions to control Kurdish demonstrators will provoke disruption and unrest within Iraq itself, particularly as Iraq continues to grapple with its own domestic political crisis. The Iranian government has demonstrated its willingness to utilise military force against Kurdish dissidents. Daily missile and drone attacks were recorded in Iraqi Kurdistan between 26 September and 7 October, conducted by members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) of Iran. Strikes were documented in Iraqi cities such as Erbil, Sulaimaniya, and Pirde, as well as refugee settlements such as Koy Sanjaq. These strikes were conducted with the explicit intention of compelling Kurdish populations on both sides of the border to cease unrest and dissent. One such strike involving the use of an Iranian drone on 28 September approached the location of a United States military base in Erbil, prompting American forces to shoot down the drone. Iran’s response to this incident threatened further retaliation should future Iranian assets be targeted by the United States in Iraq. Most alarmingly, unconfirmed reports from social media accounts and media operators within Iran indicate that ground personnel and heavy vehicles such as tanks may have begun to amass at the Iranian border with Iraq. If verified, there remains an underlying threat that military personnel may be deployed not just within Iranian territory but also within the territory of Iraqi Kurdistan. The impact on regional security by an Iranian ground incursion into Iraq would be significant, prompting a rapid deterioration in the security environment in Iraq that would draw the diplomatic attention of regional actors such as Turkey, Israel, the United States, and Saudi Arabia. The extent and purpose of any incursion would ultimately determine the level of volatility experienced within Iraq’s security environment and in the region as a whole. Iran has long projected influence into Iraqi politics, seeking to steer Iraqi foreign policy in a pro-Iranian direction by funding Iraqi political groups and controlling pro-Iran Shia militias. Indeed, newly elected Iraqi President Abdul Latif Rashid has been praised by pro-Iran groups and the Iran-backed Shia Coordination Framework for his nomination of Mohammad Shia al Sudani to the position of Prime Minister of Iraq. Any ground-based, armed intervention within Iraq is therefore likely to utilise militia groups and leverage the support of the Coordination Framework rather than escalating immediately to an overt Iranian offensive within Iraq itself.

Plausible deniability informs the logic of utilising militia groups as the first step of escalation within Iraqi Kurdistan. The Iranian regime almost certainly desires an end to dissent within its own territory and the restoration of internal stability as soon as possible and with as few concessions on their part as possible. This line of rationale may also bring Iran into diplomatic confrontation with Turkey, a country with whom Iran shares a 534-kilometre-long border. Turkish repression of Kurdish political forces both at home and in northern Iraq has attracted widespread apathy towards the Turkish state amongst the Kurdish populations of the Middle East. It is realistically possible that Iranian proxies within Iraq may be utilised to redirect Kurdish discontent away from the conduct of the Iranian regime within Iranian Kurdistan and instead towards the actions of the Turkish government via a false-flag incident.

Though this scenario remains only a possibility at present, its existence has contributed to the decision of Turkish diplomats and government officials to avoid overt criticism of the Iranian regime and its response to the demonstrations. Turkish officials are keen to attract as little attention as possible, particularly due to its domestic Kurdish population that has already displayed a willingness to engage in small-scale forms of unrest within Turkish territory in response to the ongoing protests in Iran. There is thus a risk of spill-over in Turkish territory, particularly given the prominence of women’s rights issues and secularism as topics of discussion in Turkish politics. These matters are at the heart of the protest movement in Iran, and copy-cat protests would provoke a notable shift in Turkey’s domestic security environment.

Potential disruption in Afghanistan and Pakistan

The threat of copy-cat protests and border disruption has been echoed amongst Iran’s eastern neighbours, most notably Afghanistan and Pakistan. Afghanistan’s takeover by the Taliban in 2021 has led to an erosion of civil rights, particularly amongst women. Protests conducted by Afghan women’s rights activists in solidarity with the protesters in Iran have already been recorded. Whilst these protests are small-scale, they present an additional threat to internal stability and security that has drawn the attention of the Taliban.

Pakistan’s proximity to the restive Iranian province of Sistan-Baluchistan, which lies within the wider geographical territory of Baluchistan that runs through both countries and Afghanistan, creates its own set of security risks, most notably in the form of hard-line Iranian repression of protesters in the province and the potential for discontent to spill across the border. Iran has taken the pre-emptive measure of sealing its border with Pakistan; a measure that is likely to disrupt Iran’s imports via Pakistan whilst also creating a diplomatic hurdle between Pakistan and Iran, as Pakistani workers reliant upon cross-border trade experience disruption to their daily lives. This creates the potential for flashpoints of insecurity, particularly in the form of worker unrest, along the border zone.

Potential disruption in Syria

In Syria, the effects of Iran’s domestic unrest are less pronounced at this stage. Kurdish groups remain active within Syrian territory and are engaged in a complex relationship with both Iran and Turkey, but insecurity remains heightened throughout the country because of the protracted and ongoing civil war. Turkey’s desire to conduct an offensive into Syrian territory may be influenced by any Iranian escalation within Iraqi Kurdistan or by Kurdish discontent within Turkey itself, but these risks have not yet materialised in full and are heightened over the medium rather than short term. Iran-backed paramilitary groups are reported to have launched a rocket attack on a United States military base in northeast Syria on 8 October, but attacks of this nature have occurred in the past and are largely divorced from the ongoing unrest in Iran. Nevertheless, this incident and its separation from Iran’s civil disorder represents a key element of the ongoing Iranian approach to its relationship with the United States, whereby Iran has sought to compartmentalise different points of contention and isolate them from one

another. This approach has not been adopted by the United States, with both United States President Joe Biden and Secretary of State Anthony Blinken issuing statements of condemnation in response to the suppression of internal dissent within Iran. There is an underlying risk that any sanctions or measures introduced by the United States or even the European Union to counter Iran’s suppression of protesters may force a shift in Iranian diplomacy and undermine existing regional security efforts such as the ongoing discussions regarding the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on the Iran nuclear program.

Israel and Iran have participated in an ongoing cold war against one another for several decades and, as such, Israel is likely to lend verbal support to the demonstrators in Iran in line with its response to previous waves of unrest in Iran. Iran has already labelled Israel as one of the foreign actors allegedly involved in co-ordinating the unrest within Iran, and a display of force against Israel – such as a cyberattack or the agitation of Iranian proxies across the Middle East – should be anticipated over the short-to-medium term. Israel is unlikely to take a more active role in promoting unrest in Iran ahead of the Israeli general elections on 1 November, with political bandwidth currently occupied by concluding a maritime border agreement with Lebanon and security force operations in the West Bank. However, a more forceful Israeli response should be anticipated in the event of a wider deterioration in the regional security environment or specific action against Israeli interests, but relations between Israel and the Iranian regime are almost certain to remain negative and follow pre-existing patterns of escalation established over the past decade.

Saudi Arabia has been targeted by Iran’s diplomatic campaign against alleged foreign actors within Iran. The London-based television channel known as Iran International has been accused by the Iranian government of receiving funding from the Saudi government. This media platform has played a role in encouraging dissent within Iran, and as such Iran has utilised its pre-existing tensions with Saudi Arabia to shift the public blame for the unrest once again away from Iran’s internal conduct and instead onto the actions of its regional enemies and opposition. Iran-backed Houthi rebels confirmed on 2 October that a pre-existing truce with the Saudi-led coalition Yemen would cease to apply, potentially opening an avenue for strikes on Saudi facilities by Houthi rockets and drones. Though this may be unrelated to the tense diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia over Iran’s internal unrest, it nonetheless highlights the degree to which Iran is prepared to undertake measures that run counter to Saudi Arabia’s security in pursuit of its own interests at this current juncture. The states of the Persian Gulf, divided between Saudi Arabia and Iran, are likely to be torn between any escalation between the two states over Saudi Arabia’s alleged role in Iranian domestic affairs.

Lastly, there is an outstanding risk to regional oil production and global hydrocarbon markets emanating from Iran’s internal instability. The decision of workers within the petroleum industry to participate in strike action in solidarity with protesters marks a shift in tactics that, if sustained, is likely to dent Iranian oil production capabilities and its output of fossil fuel products at a time when the global economy is experiencing an energy crisis. The regional spill-over of such an incident would be limited due to sanctions on Iran’s ability to sell petroleum products on the global market, but such a move would nonetheless add to the strain between Iran, Saudi Arabia, and other oil-producing states within the region that may reasonably compound upon risks of insecurity that could emerge as a result of Iran’s domestic crisis.

Short-term forecast

Unrest in Iran is unlikely to subside in the short-term and will likely expand geographically in the coming days as commercial and industrial protest groups increasingly seek to coordinate activities between regions. The Iranian government has resisted a severe crackdown in line with previous uprisings due to the geographical spread and cross-sectional makeup of the societal groups involved in the demonstrations, but the use of force by security personnel has become commonplace and messaging by the Iranian government remains primarily aimed at the domestic security apparatus rather than the wider population. Iran’s regime is highly likely to continue to suggest that foreign actors are responsible for the unrest, utilising the civil disturbances as a pretence to engage in belligerent behaviour abroad and expand crackdowns on internal political opponents.

The demands of protesters are unlikely to be met in the short-term due to the above factors. The Iranian government is likely to offer minor adjustments to policies in an attempt to placate demonstrators to more manageable levels, but significant policy changes from the Iranian state should be considered highly unlikely in the short term absent a dramatic escalation in the political and security environment. As such, the underlying conditions promoting unrest are likely to continue over the short-term, and public dissatisfaction has demonstrated a capacity to snowball and remain sustained rather than decrease as time passes from the death of Mahsa Amini and the cause of the original unrest.

At the regional level, Iran’s long-time opponents are likely to continue to utilise the unrest as an opportunity to advance their own interests. States sharing a border with Iran are likely to pursue strategies aimed at maintaining border integrity and resisting the spread of unrest into their own territories. Of Iran’s border states, Iraq is the most likely to experience significant volatility in the short-term due to its large Kurdish population, Iran’s influence in-country, and its poor ability to control and project power across its territory. Unrest within Iraqi Kurdistan should therefore be anticipated in the short-term, with the potential for further escalation and limited violence.

Western policymakers are also likely to come under increasing pressure to demonstrate support for protesters in Iran, particularly whilst violence continues to be deployed against demonstrators. The causes of women’s rights and secularisation (or, at the least, freedom from overt theocratic law-making) are considered foundational to many Western nations and their domestic populations. Protests organised by the Iranian diaspora and by sympathetic members of the public have already been documented in several Western nations, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, and France. A scenario whereby public and political pressure results in further sanctions against members of the Iranian security apparatus should not be discounted, particularly as Iran engages in behaviour in other areas of policy that may attract retaliation from Western nations. In the event of further sanctions targeting the wider Iranian state, security apparatus, or IRGC, there exists the realistic possibility of further regional escalation as Iran responds to measures perceived to be supporting forces undermining the legitimacy of the regime.

Tailored reports to mitigate risk from disruption

Increase your operational resilience with bespoke reports. Forward-looking intelligence can identify and help mitigate global risks that could affect your organisation.