Biden Foreign Policy at 100 Days

28 Apr 2021

This week, President Joe Biden celebrates his 100th day in office. When the new president took office in early January, domestic issues were treated as a priority. The country had seen the Capitol building stormed and was facing a dramatic surge in COVID-19 cases. His first hundred days have thus seen a spotlight on resolving these domestic issues.

Executive Summary

When President Joe Biden took office in early January, domestic issues were treated as a priority. The country had seen the Capitol building stormed and was facing a dramatic surge in COVID-19 cases. His first hundred days have thus seen a spotlight on resolving these domestic issues. As a result, foreign policy was less defined. One of Biden’s mantras, however, has been that any American foreign policy must always start and end at home. To this end, this domestic focus has helped shape his initial foreign policy.

Notably, a course reversal on a number of the Trump era’s foreign policy elements, something that has been seen as a welcome return to “normal” for many US allies and friends. There has also been the declaration of the end of the “forever wars” in the Middle East, in particular Afghanistan. There have, however, been a continuation of a number of policies and goals driven initially by Trump. Notably the growing push to re-orientate American foreign policy to meet emerging international and global problems such as a more aggressive and authoritarian China.

Under Biden, the US has also re-joined the World Health Organisation and has pledged 4 billion USD to the global vaccine scheme, helping to revitalise US leadership in the global health arena. What, however, will these changes in both the domestic and foreign policy mean going forward?

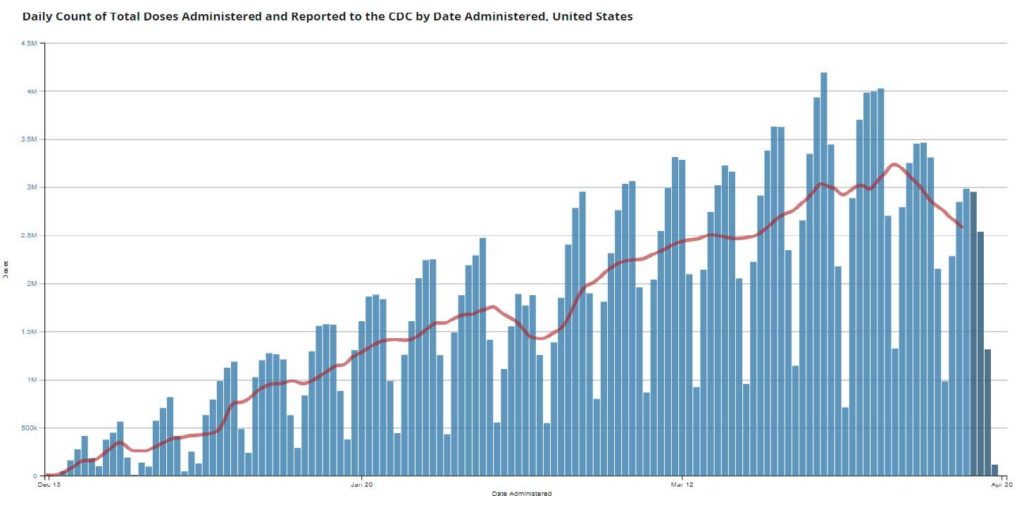

Foreign Policy Starts at Home

President Joe Biden’s first 100 days have arguably been quite successful. The vaccine drive, started under his predecessor, has continued with over 100 million Americans having now been vaccinated. A 1.9 trillion USD economy recovery act has also been passed and work is underway to try and address the reasons for the divides in American society. For Biden, these domestic policies are vital to American foreign policy and soft power. Without them, US foreign policy cannot be a success. The most poignant example being America’s leadership in the fight against COVID-19. The US domestic successes in vaccine programmes, alongside other moves, will help the US credibly regain leadership in global health following the poor initial reaction to the pandemic.

This idea that “foreign policy starts at home” was alluded to by Biden on the campaign trail. The new president often suggested the idea that American foreign policy can no longer be seen as being removed or self-contained from US domestic policy. Even prior to Trump, much of the US foreign policy had grown more detached from the interests of working- and middle-class Americans. Biden believes that this rift between the interests of American citizens and the last quarter of a century of American foreign policy has helped lead America to several of its current domestic issues. These issues are many and varied but include: the hollowing-out of its middle class, historically excessive wealth concentration, the success of a few major cities at the expense of vast areas of America, and a growing disillusionment with democracy and American institutions.

This idea that foreign policy starts at home, is not new, indeed it is a reversion to an older ideal. In 1946, as the United States began to enter the Cold War period, the US diplomat George Kennan stated that every measure solving internal problems was a foreign policy victory over Moscow. The wider foreign policy agenda regarding China is now beginning to have many similarities with the early Cold War, and domestic performance will be as equally important. Biden is also the first President in recent years who does not believe in trying to “reset relations” with Russia, and instead has stated under him, the US will no longer “roll over” to Russia. Russia adding the US to its list of “unfriendly states” only serves to heighten the idea that such inter-state competition is returning.

Part of this realisation that foreign policy begins at home is the fact that American foreign policy rests as much on its image and soft power as it does hard power, negotiators and diplomats. America, and its ideals, are often seen as being the “shining city on the hill” that many nations, and people across the world aspire to. This soft power has been in decline for some time, with the 2003 invasion of Iraq often cited as a correlating factor. The images of the storming of the capitol building in January 2021 for many international observers only served to further undermine American soft power. The idea of America having a violent transition of power between presidents, also provided much propaganda value for the authoritarian states around the world. China and Russia were able to “showcase” a democracy in decline and the “violence and chaos of liberal democracy” against their own perceived stability.

Biden has gone about these changes, and policy implementations, which can be said to be transformative, quietly, and with little fanfare. Indeed, compared to his direct predecessor, much of what Biden has done, will be seen as positive by the wider international community. Biden has acted with speed and authority in enacting a number of key new domestic policies, and also with regards to the way in which US foreign policy is being once again dealt with. His pandemic response package is already helping to drive the global economic recovery, for America is still a primary stimulator of global economic growth. Indeed, Oxford Economics state the US will be the largest single contributor to global growth for the first time since 2005.

Most notable is the fact that the US president is once again no longer communicating through Twitter. It is likely that he is aided in these changes by his many years of service within the DC beltway, 44 years as Senator and Vice President. His years of political experience have likely given him an intimate knowledge of US domestic and foreign politics which will no doubt serve him well through his term of office.

Back to Basics

The election of Biden contrasts greatly with Trump. For many, this is seen as the US shift back to “normality”. The new president is more traditional and has emphasized a return in the use of the State Department and the American Foreign Service, relying less on person-to-person contact, as Trump did.

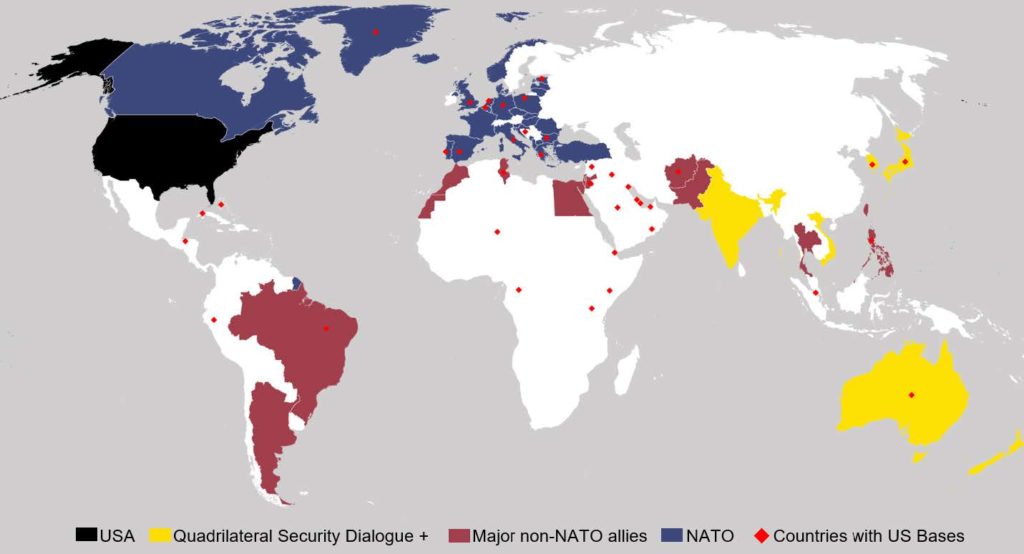

Biden, in February 2021, stated that American commitment to NATO was “unshakeable”, that “America was back” and committed to reengaging with its allies and partners. Other signs of a reversing of Trump’s doctrine include Biden’s re-joining the Paris Climate Agreement, the US re-joining the World Health Organisation, and statements given to allies and partners in Asia such as Japan. However, Biden has also continued much of what Trump started regarding China, Iran, Russia and Israel. Whilst he has also recommitted to NATO, he is unlikely to cease demands that other NATO members pay their fair share and will likely continue the opposition both Obama and Trump had to voice over the controversial Russo-German Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

China is notable in that both Biden and Trump have based much of their foreign policy towards the country. In a bid to restructure US foreign policy towards Asia and China, both Biden and Trump have been supportive of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, more commonly known as “The Quad”. This multi-lateral alliance includes Japan, India, Australia, and the US. It is geared to establish a free and open Indo-Pacific in the face of increasing Chinese aggression. The Quad, which was initiated by Japan in 2007, ceased in 2010 after the Australians withdraw. However, at the 2017 ASEAN summit, the Quad was revived by Donald Trump with the agreement of the other former members “in order to counter China militarily and diplomatically”. Biden has already indicated he wishes to continue to strengthen it. In 2020 the Quad+ met for the first time, and in 2021 members of the alliance declared their support for a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” and a “rules-based maritime order in the East and South China Seas”. Under Biden, a March 2021 meeting of the Quad discussed how the alliance plus other allied countries in the region could look to become an “Asian NATO”.

As stated, under Biden, the US State Department and Foreign Service are seeing renewed attention. During the Trump administration, around 50 percent of all positions in the State Department were technically vacant, including several directly related to foreign policy and decision-making. The Biden Administration has made it clear that it wishes to rebuild the State Department. The new president has been quick in nominating credible and well-regarded people to the department’s top positions. Perhaps due to this renewed attention, applications for the Foreign Service officer test have jumped 30 percent compared to under the Trump Administration. Applications in recent years had declined, leading to fears that in later years the department would have a shortage of trained diplomats, negotiators and top officials.

The End of the Forever War

The most notable statement of Biden’s foreign policy in his first hundred days has been his declaration of the end of “forever wars”, most notably that of Afghanistan. Both former presidents Obama and Trump wanted to end the Afghanistan War, and both were unable to. Indeed, the US interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq have many critics. The Afghan war alone has cost the US Treasury in excess of 2 trillion USD since 2001, and the loss of over 2,000 US lives. Despite this cost in blood and treasure few of the humanitarian objectives or war objectives in the country have been achieved in the last two decades. In this context the US withdrawal makes sense. It will, however, concern allies, such as Ukraine and Taiwan, that America is willing to abandon a close regional partner to potentially fall to their main enemy in the conflict.

The reasons for staying in Afghanistan included noble ones such as trying to build an Afghan state and protecting human rights. However, Biden has clearly signalled that he believes the cost of continuing in Afghanistan outweighs the benefits. He also pointed out that the end of “boots on the ground” would not equate to the ending of US support in non-military ways for the Afghan peace process and the increasingly embattled Kabul government.

Come September, a full-scale Taliban takeover of what remains under Afghan government control is a highly likely scenario. For Afghanis who have worked with the US government or enjoyed newly found tentative liberal democratic freedoms in the major Afghan cities, such a takeover will undoubtedly mean fleeing or being executed.

Whilst Biden is focusing on the end of the war, and the ongoing peace negotiations in Qatar with the Taliban, and the Afghan government, international observers may well see it differently. They may well see the pull-out and subsequent events in Afghanistan as a second Vietnam moment, colouring their view of US foreign policies and commitments to allies. For countries such as Taiwan and Ukraine where US security guarantees are deliberately vague, the image of a US-backed government falling months after the US withdraws support will frame their perceptions of the end of the US war in Afghanistan, and such a perception may mean the US foreign policy has to be recalibrated to some degree to try and offset the negative connotations associated with this.

Looking Ahead

Biden’s foreign policy has some key elements which when taken together offer a glimpse into the future of US foreign policy under the new president, and some of the key challenges he thinks the US will need to focus on in the near to medium future.

The end of “boots on the ground” in Afghanistan is perhaps the most major foreign policy shift. If, because of this, the Afghan government collapses, then it will likely complicate Biden’s future efforts with regards to security guarantees for other US allies and may well leave a feeling of global US retrenchment similar to after the fall of Saigon. Indeed, it is believed that the real costs involved in leaving Afghanistan would be the US’s global standing and prestige. This feeling may well be heightened due to the expansion of Chinese foreign influence. Within Biden’s calculus is that perhaps the best time to make such a costly move would be after four years of a president who has already thrown much of these questions into sharp focus, and that after such a move has been made the rest of his term can be spent rebuilding America’s global standing.

It must be emphasized however that the ending of the War in Afghanistan does not necessarily mean the end of the wider US “War on Terror”. Targeted US drone strikes and US support for other global counter-terror missions is likely to be maintained, for the US still perceive the global threat of terror as a direct security threat to their domestic safety. This means that drone strikes will likely continue, as will US assistance for interventions such as the French-led stabilisation in Mali. It is also likely that a number of other nations with growing terror problems, such as those in West Africa as looked at in our advisories on the region, and Somalia, may see greater US engagement.

Biden has thus decided that the cost of leaving Afghanistan is bearable in the long term. He likely even feels the cost will be smaller than the value it will give to the country’s foreign policy. Especially as the US reorientates away from the Middle East and focuses more on the threat it, and its allies, will face in the coming years.

Other credible threats Biden believes US foreign policy needs to counter include rising authoritarianism, the global impact of climate change, and the potential battle for ideas between liberalism and illiberalism. The increasing aggression of China and Russia on the world stage, and the growing public awareness and mounting costs of climate change highlights the potential truth to this vision.

Biden was involved in the last major contest of global ideas and knows the major ways in which the US won it. Namely through working with allies and global partner nations, and in also making sure that the domestic US front is united, willing and able to sustain such a contest over a long period of time. In trying to rebuild domestic US society and infrastructure, it highlights he believes that the US’s next foreign policy challenges will be more akin to those found during the mid to late 20th century.

In essence, Biden’s foreign policy can be said to be a recalibration towards generating the necessary domestic strength and international good will and allyship needed for a potential prolonged global contest of ideas. Such internal strength and network of allies will also be vital as other challenges impact the US, notably that of climate change, the impact of globalisation and the ever-increasing importance of technology. At the time of writing how Biden intends to try and manage such a balancing act is unclear. In a number of keyways, however, Biden’s long term foreign policy will look similar to that of his predecessor. Central to this is the belief in a forthcoming great power contest and a battle of ideas. As evidenced, however, with his overtures to key allies, Biden is likely to approach the challenges in a more traditional manner than that of his predecessor.