DRC Ebola Outbreak: Operating in the Hot Zone

14 Nov 2018

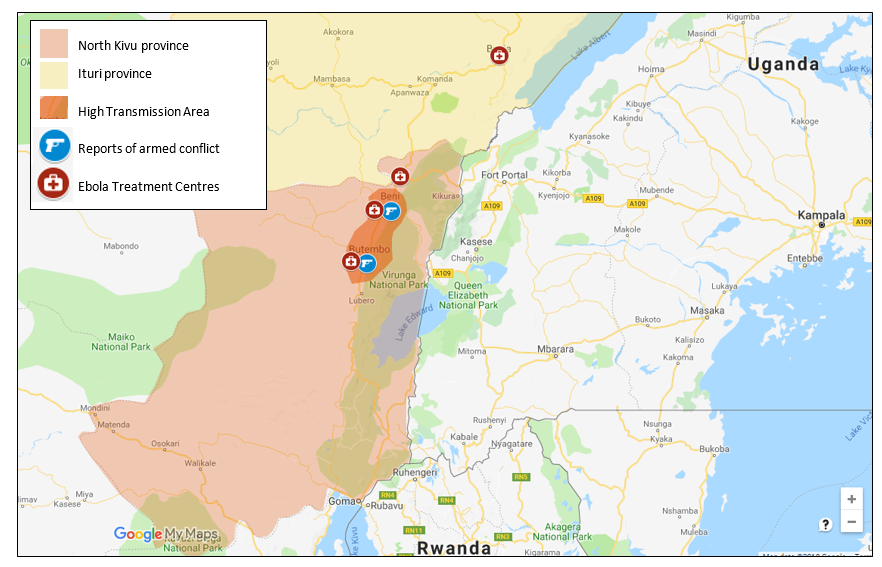

The recent outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in North Kivu and Ituri border provinces in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) continues to gather pace as the international response is hampered by ongoing militancy in the affected areas.As of 11 November, a total of 329 EVD cases (294 confirmed and 35 probable) have been reported, leading to 205 deaths. Those in, or travelling to, eastern DRC should receive an independent medical training, focusing on transmission control as well as community engagement. Travellers should also receive a briefing and mitigation advice on the prevailing security threats. Travel Risk Managers should have clear emergency protocols and escalation strategies in travel risk plans, and consider the variable international guidance on safe staff repatriation from Ebola affected areas following the end of deployment periods.

KEY POINTS

- The recent outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in North Kivu and Ituri border provinces in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) continues to gather pace as the international response is hampered by ongoing militancy in the affected areas.

- As of 11 November, a total of 329 EVD cases (294 confirmed and 35 probable) have been reported, leading to 205 deaths.

- Those in, or travelling to, eastern DRC should receive an independent medical training, focusing on transmission control as well as community engagement. Travellers should also receive a briefing and mitigation advice on the prevailing security threats.

- Travel Risk Managers should have clear emergency protocols and escalation strategies in travel risk plans, and consider the variable international guidance on safe staff repatriation from Ebola affected areas following the end of deployment periods.

SITUATIONAL SUMMARY

Health/Armed Conflict: The director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on 5 November warned that the current Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak is at risk of becoming entrenched in the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), exceeding the capacity of international public health organisations to bring the outbreak under control. This latest development comes as international organisations are facing greater security threats and difficulties ensuring the protection of their staff, leading to some organisations opting to suspend their operations.

As violence in the North Kivu province has escalated, in some cases targeting health workers, both the Congolese Ministry of Health and international responding organisations are increasingly unable to access communities in some of the worst hit areas leading to the Ebola case rate to double in October from the previous month. Longstanding government mistrust in Ituri and North Kivu provinces has resulted in local communities remaining resistant to seeking treatment in the affected area. The Congolese Ministry of Health (MoH), who are leading the response to the current Ebola crisis alongside international partners such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), are using military assets to support their response measures, further exacerbating local engagement issues. The use of military assets has further exacerbated tensions in the region due to historic allegations of human rights abuses.

THREAT ASSESSMENT

The EVD crisis unfolding in eastern Congo presents significant challenges for staff operating in the area. At this time, the outbreak currently remains contained in the two border provinces of Ituri and North Kivu; mainly due to the rapid and effective infection control measures taken by neighbouring countries. However, the virus is becoming increasingly entrenched within the infected provinces due to ongoing access and security issues. Currently, both Butembo (town) and Beni (city, both North Kivu) are the most affected as the ongoing insurgency is resulting in Ebola transmissions escalating while public health access remains severely limited. Multiple militias remain active in the border regions with Uganda and Rwanda, presenting insurmountable obstacles for international organisations in delivering an effective response. Additionally, longstanding local mistrust of the Congolese government and military entities has reduced the engagement of local communities seeking medical treatment and adapting to new transmission control behaviours.

Over the last six weeks there has been an increase in the specific targeting of medical response teams in North Kivu province leading to the withdrawal of international response teams and disruption to Ebola treatment programmes. Two public health workers operating alongside the Congolese military were fatally shot on 20 October by militants in Butembo city (North Kivu) after militants opened fire on their position. On 2 October, two national Red Cross workers were attacked in Butembo by a local community after assisting in the implementation of safe burial procedures at a local boy’s funeral. The crowd became hostile after the boy’s father told the burial team that he did not want his son’s body treated in such a way that contravenes local burial customs.

Violence has also continued in North Kivu as militant groups have used the escalating crisis to launch attacks on security forces and civilians. On 10 November suspected Ugandan rebels associated with the Islamist militant group, the Allied Democratic Forces, killed six people and kidnapped five children in the Mayimoya commune, Beni (North Kivu province). Earlier in the day, Mai Mai rebels, a militant group initially established by local communities to protect civilians and livestock from other armed groups, attacked a military camp in Beni, killing one soldier. Intensifying violence in Beni has led to several major international aid agencies suspending their operations in the city.

Operating constraints remain the most serious challenge for international responding organisations in Ebola-affected regions. The two provinces (Ituri and North Kivu) are remote, with limited communication and poor transport infrastructure. Both governance and health services are severely limited in the region, which has led to longstanding cultural practice to dominate local communities’ response to transmission control. In recent days Ebola health workers in Ituri province have gone on strike due to arrears in government payments, highlighting the challenging and tense environment organisational employees face and the limited governance in the affected provinces. The strikes have led to huge delays at Ebola screening checkpoints, further increasing the risk of transmission.

The Ebola response has led to a period of heightened tension, creating adverse security implications for response staff operating on the ground. Between 2014 and 2016 a series of civilian massacres left 700 dead in Beni, with many rights groups alleging that the Congolese military were complicit in the attacks leading to longstanding fear of the military amongst local residents. The use of military-run health units has further exacerbated these local tensions with residents remaining fearful of engaging with such government-run units. Humanitarian organisations also face a conundrum in associating with the government as it limits their appearance of neutrality and independence, increasing their association with the government. The current operating context has resulted in significant disruption to the current Ebola treatment and vaccination programmes, leading to the UN security council issuing a resolution calling for the immediate end to hostilities and the targeting of health facilities and workers.

DELIVERING AN OPERATIONAL STRATEGY

Eastern DRC presents an increasing complex environment for organisations with a staff presence in the region. Any operations must consider the multiple risks to employees on the ground and develop strategies to minimise their vulnerability. In order to achieve this, organisations should consider using a threat analysis model, that considers both threats posed by the environment, the vulnerability of operating in the area (both reputational and personnel focused), and finally considers a remediation approach once threats and vulnerabilities have been identified. This process is a pre-emptive and continuous cycle that is constantly reassessing threats and vulnerabilities to ensure remediation strategies are implemented as soon as potential risks are detected. This process can support organisations making timely and appropriate decisions that focus on duty of care towards their employees while also building organisational resilience and sustainability of operations.

Threat detection: There are a multitude of threats facing organisations deploying to or with staff in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, DRC at the current time. To simplify the process this advisory will look at the most pertinent threats related to the EVD Crisis; however, when developing an operational threat and vulnerability assessment, it is important to consider the full spectrum of threats in your analysis.

- Employee exposure to EVD: An employee being exposed to EVD through contact with affected communities or individuals.

- Return transmission risk: An employee contracting EVD and returning to home location during incubation period.

- Violence: The risk being directly or indirectly involved in an armed confrontation between militant groups or militants and the armed forces.

- Humanitarian access: The risk of employees being directly targeted for being part of the government-led response to the disease.

Vulnerability detection: Every organisation will have attributes that make it vulnerable to the specific threats posed by the EVD outbreak in DRC. By identifying these vulnerabilities (be it structural, geographical or technological) weaknesses can be understood and therefore strategies implemented to reduce such vulnerabilities

- Lack of experience in the operating environment: One of the biggest vulnerability’s organisations will face is deploying staff to the crisis who lack the relevant in country experience, however, given the demand for deployed staff, strategies must be developed to improve situational awareness.

- Information networks: Normal information networks in eastern Congo are reactive rather than proactive, meaning that critical information on security incidents in the two provinces is slow to reach travel risks managers.

- Emergency protocols and 24-hour response management: Lack of staff understanding of what to do in a crisis, and minimal resourcing for 24-hour organisational support.

Threat and vulnerability remediation: Remediation can take place once a threat and vulnerability issues have been successfully identified. This process will help guide the security plan and isolate, mitigate and resolve vulnerabilities through effective remedial actions such as planning, policy and procedures and training.

| Threat | Remedial Action |

| Employee exposure to EVD | Have pre-existing policy and procedures in place that minimises the threat of employee exposure to the virus. This should include a clear briefing on the medical risks, symptoms, transmission control and personal protective equipment (PPE) so employees understand potential exposure threats. There should be a clear organisational procedure of what to do in the event a member of staff believes they have been directly exposed to EVD including a medical evacuation plan. |

| Return transmission risk | Staff should be aware of what to do in the event they become symptomatic once they return to their home location following deployment. The incubation period for EVD is 21 days so staff should remain vigilant throughout this period. Staff should not travel if they are sick. Most ports of entry/exit will have screening measures and employees could be quarantined if displaying any EVD symptoms. |

| Targeted militant violence | A constant feature of the current crisis is the high levels of targeted violence towards international organisations who are currently involved in government-led EVD response. Organisations should consider the additional risks and develop clear guidance on what action should be taken if staff feel that community animosity is building towards organisational activities or staff. Any reports of targeted threats should be logged and managed by the appointed security focal point. These should be periodically reviewed by a centralised security team and an assessment made on whether operations should continue if there is a serious threat. |

| Humanitarian access | It is central that any organisation currently working in eastern DRC maintains awareness of how they are perceived in the area where they work. Access to affected communities should not be taken for granted. Funding and time should be allocated to establishing and maintaining good relations with local communities via community leaders. This will support access negotiations for actors in the provinces but also mitigate possible future threats coming from the community. |

| Vulnerability | Remedial Action |

| Lack of experience in the operating environment | The DRC Ebola crisis led to a surge in international staffing to the affected area. Due to the complexity of the crisis, ideally such staff should be experienced staff with local level experience. However, if staff come with limited experience, organisations must fully prepare their staff for the operating environment. This should include medical and transmission training alongside security awareness training that focuses on improving the situational understanding of the ground environment. If employees are already deployed, use their experience of the operating environment to help further staff prepare for deployments. |

| Information networks | Developing a local level information network should be considered a critical element to building more resilient operations, that can respond and evaluate threats quickly. In the DRC, network and safety organisations exist who can support you in building local level networks. The complex ground environment means that these networks will be essential in negotiating access to certain areas, building critical ground intelligence and developing relationships with communities. |

| Emergency protocols and 24-hour response management | In the event of an emergency, staff should be prepared and trained to respond according to a pre-defined operating policy. Incident management systems should be established ensuring staff have access to 24/7 emergency operations centre who are able to respond quickly to support the situation. Emergency plans and concept of operations should be activated, and given the magnitude of the event, should be followed to ensure safe access to medical care, relocation or evacuation. |

SECURITY ADVICE

HealthSevereMedical: Staff deploying should be fully briefed on the medical risks in the DRC and should be trained on how to minimise the risk of transmission, including the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Pre-identify high risk activities, such as field visits, funerals and operating in EVD treatment centres, and attempt to minimise staff exposure to such activities.

Security: Staff should understand what to do in the event if an escalation occurs and have clearly defined emergency points of contact that they can ring in the event of an emergency. Prioritise building networks with other organisations in the area with clear information sharing arrangements. Remain up to date with the latest location specific security information and trends by monitoring news sources and security alerts.

Accommodation: Criminal attacks on organisational compounds and international staff housing do occur in eastern DRC. All accommodation should be sought in secure housing compounds with clear and visible security measures that will mitigate the potential of the compound being targeted. This should include a perimeter wall, visible 24/7 security presence, CCTV, metal doors and strong visible locks as well as access to multiple communications devices with a dedicated phone number for emergencies.

Secure travel: Any travel outside the accommodation area should be planned ahead of time and risk assessed alongside a security trained focal point.